Guillermo del Toro might be the best possible filmmaker to tell the story of Frankenstein.

A core pillar of the director’s oeuvre is literal and figurative monstrosity. One glance at his filmography and you sense that he’s been working his entire career to tackle fiction’s most famous monster. (He has been developing an adaptation since at least 2008.) Now, with a blank check from Netflix and a top-notch cast, del Toro is ready to introduce his monster to a world that could probably use a fictional one to help them process the ones that are running across the global zeitgeist. The expectations are naturally high, considering the filmmaker’s considerable bona fides, his stated interests, and Frankenstein’s status in popular culture. For someone who could easily be considered cinema’s foremost expert on monsters, what is his entry point? How does he bring Mary Shelley’s enduring story to a new generation?

Del Toro starts with a group of sailors stranded in a frozen sea. As they try to dislodge their ship and get back on course, they discover a half-alive Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac) in the snow. Frankenstein is on the run from his greatest creation and his biggest regret: his Creature (Jacob Elordi). The furious monster eventually reaches the stranded ship and uses his superhuman physicality to try to push past its defenses to get Victor. As the soldiers try to ward off the monster, Victor tells his story to the captain, “Part 1” of Frankenstein. His part is defined by unchecked ambition, dubious morality and ethics, unrequited love, and remarkable cruelty. From Victor’s perspective, he was a victim of his genius and wanted to right his mistakes of toying with the powers of a god, if he could escape his creation.

At first blush, Victor’s perspective is compelling. Del Toro’s direction of the monster’s battle with the soldiers is frenetic, the set piece’s extraordinary scale making you believe in the Creature’s destructive capabilities. When we enter Victor’s past, del Toro crafts a gorgeous gothic landscape of bold, contrasting colors that reflect Victor’s volatility. He’s especially fond of how red clashes with his tans, whites, and greys. That clash conveys otherworldly beauty, debilitating loss, and sterile interpersonal connections. Looking around at the ornate but icy intricacies surrounding him, Victor’s embrace of the sacrilegious and the macabre makes twisted sense. Oscar Isaac conceives that tricky dynamic very well. His face and body are constantly teetering on the edge of madness, but his tight control allows him to avoid dissolving into unseemly caricature. Via Isaac and del Toro’s thoughtful touches, you can empathize with Victor’s heroic conception of himself.

However, empathy does not mean absolution in Frankenstein. He holds Victor accountable for his excesses by highlighting his darker traits: his extraordinary ego, intellectual posturing, and indifference to human suffering. He finds an excellent foil in Elizabeth (Mia Goth), whose mockery of Victor’s worst instincts leads him to see her as a potential love match, while we know better. Del Toro elegantly weaves between Victor’s courting of Elizabeth, his experiments to “conquer death,” and the monster’s dogged efforts to reach him. While not necessarily a cause-and-effect map, del Toro lays enough of a path to direct us to the conclusion that Victor’s story of monstrous creation is more autobiographical than he realizes. When a stunning crash of electricity brings the Creature to life, and Victor responds with a repugnant mix of pride, frustration, and callousness, his villainy is indisputable. Understandable, considering his circumstances, but indisputable.

As fascinating as Victor is, Frankenstein is as much about the monster as the man (or, rather, human). Instead of delaying the inevitability of the Creature exacting his long-sought revenge on Victor, del Toro brings the confrontation up to its halfway point. “Part 2” belongs to the Creature, as he presents his case to the captain serving as judge in this psychological civil suit. We follow the Creature from where Victor left off, alone in a world that doesn’t know that his existence is possible and that he barely understands. His journey takes him to a wintry farm, where he observes a close-knit family and learns from them. In return, he utilizes his supernatural abilities to secretly aid them, leading them to regard him as an unseen forest spirit. Again, del Toro is methodical and meditative in exploring the same beautiful, brutal world through the Creature’s eyes.

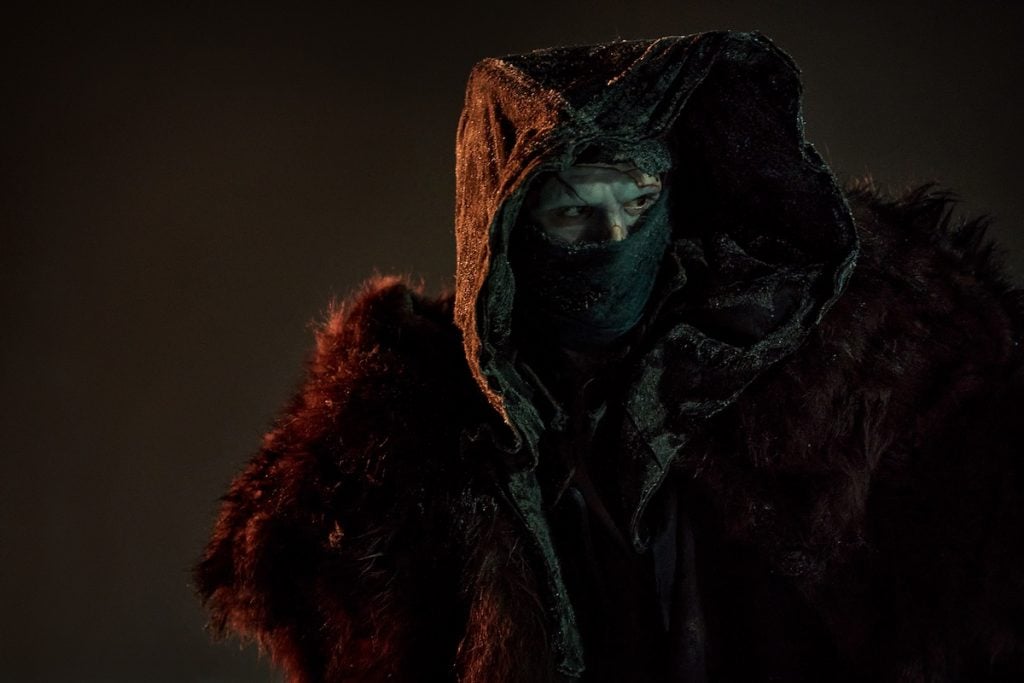

Unlike Victor, the Creature doesn’t internalize the world’s abuses and turn them into self-indulgent weapons. Despite Victor’s inhumane abuses, the Creature retains an openhearted innocence. You see and feel it every time Jacob Elordi moves within a frame, his limbs bearing an ungainly tentativeness, reflecting the Creature’s curiosity and his embarrassment at taking up space. When the Creature interacts with Elizabeth and the farm family’s blind, elderly patriarch, Elordi’s eyes gleam with hope that they can perceive him beyond his pallid exterior, and subtle excitement when they do. Naturally, the Creature is subject to more mistreatment and tragedy throughout his version of events – some purposeful, some unintentional – but his embrace of humanity is steadfast. Elordi never loses that thread, not amidst pounds of makeup and costumes, nor when he fully embodies the Creature’s inherent rage. His performance is one of intense empathy and a new landmark in the monster genre.

Like del Toro’s other works, Frankenstein is about the nature and nurture of monstrosity. Victor and the Creature are both products of a beautifully superficial world where nuance is lost to rash conclusions and revulsion of the unknown. Del Toro grants them both complex portraits to understand what made them and how easily they can be misread. What those portraits unveil is that monstrosity lies within the ego. Victor is a man of self-made mythology, which makes it easier for the world to crush and curdle his insides. The Creature has no ego, which shields his humanity from the world’s trespasses against him. Relentless compassion is what makes the difference in how they’re nurtured and how their intertwined stories end. Mary Shelley’s indelible creation serves as del Toro’s comprehensive statement on how empathy tempers our monstrous instincts.

While not a novel insight into monstrosity, Guillermo del Toro, as he was to tell Frankenstein’s story, was the best filmmaker to present the most definitive version.

Frankenstein held its North American Premiere as part of the Special Presentations section at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival. The film will have a limited theatrical release starting on October 24th, with a Netflix release on November 7th.

Director: Guillermo del Toro

Screenwriter: Guillermo del Toro

Rated: R

Runtime: 149m

While not a novel insight into monstrosity, Guillermo del Toro, as he was to tell Frankenstein’s story, was the best filmmaker to present the most definitive version.

-

GVN Rating 9

-

User Ratings (1 Votes)

10

A late-stage millennial lover of most things related to pop culture. Becomes irrationally irritated by Oscar predictions that don’t come true.