The twenty-first century has introduced curious intersections between film and theater. There has been a rise in professionally recorded productions (Hamilton, Waitress, the upcoming Merrily We Roll Along), narrative dramas that implement performance (Sing Sing, Ghostlight), and even staged productions that use video as an on-stage tool (see the works of Ivo Van Hove and Daniel Fish). Sometimes, the mediums converge together in ways that complement both their forms and functions. Other times, they feel diametrically opposed in a way that is intentional, suggesting something voyeuristic and raw. What is the merit of one versus the other and what insight can be found through their connection?

This is the lens through which playwright Jeremy O. Harris explores the topic in his new documentary, Slave Play. Not a Movie. A Play.. As the title would suggest, the film is directly in conversation with Harris’ groundbreaking play, Slave Play, which sees three interracial couples exploring their racial disparity and emotional dysfunction through a form of couples therapy that has them reenacting Antebellum-era slavery as sexual roleplay. The show, which loads its first act with a flagrantly kinky triptych of sex scenes, caused quite a stir on Broadway for its racy sexual content (in more ways than one). It garnered a vocal minority of detractors – both Black and otherwise – who found the play offensive and exploitative. However, many others found the play revolutionary in its platforming of modern Black identity within the American theater.

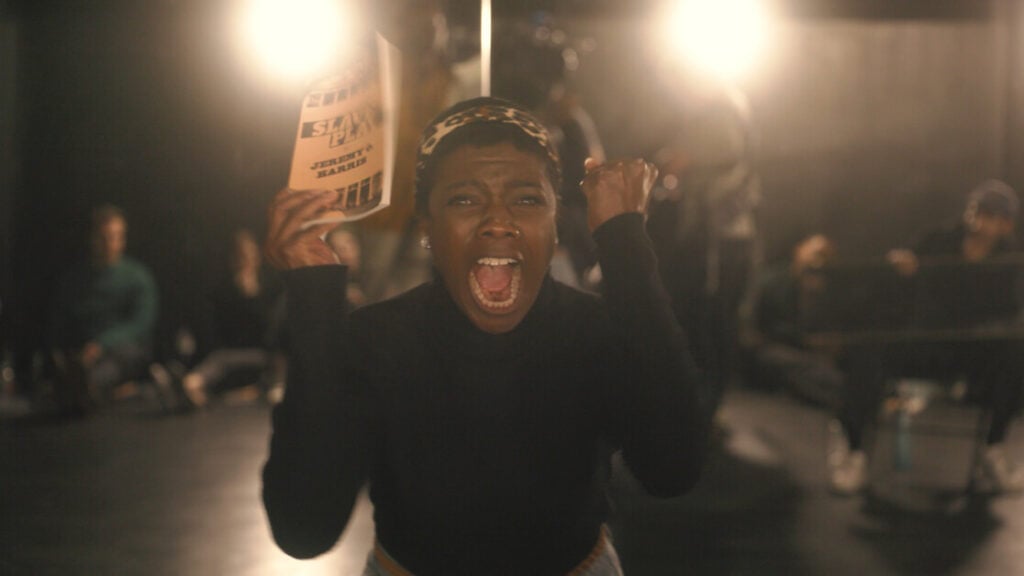

Those unfamiliar with Slave Play will glean insight into all of this right from the jump (though the story’s more scanty details are teased out gradually, like in the original play), however Harris’ new documentary takes place after its Broadway run, which bowed in 2021. The film begins a year later as Harris gathers an entirely new group of actors, some performing the same character, to workshop the piece further – not such a common practice for a show that has already bowed on Broadway twice and been nominated for 12 Tony Awards. However, Harris is not a common writer; theater fans already know that his views on the industry are radical and his modes of creation are experimental. As he directs his actors and explains the meaning behind his words, it’s clear he is comfortable venturing into the unknown, perhaps even the futile. In fact, the entire film itself is introduced as one big confusing experiment with no concrete objective; when showing the film’s progress to one of the original Broadway cast members, they ask Harris what he thinks he will get out of making the film. Harris, humorously and luminously, has no answer.

What’s surprising about this is that anybody who has seen Slave Play will tell you that, whether you enjoyed the play or not, Harris’ voice as a writer is a pointed one. The entire work is an incisive take on white saviorism and suppressed Black identity. Though it certainly provokes audiences with no easy answers, Slave Play isn’t merely taking shots in the dark. It feels like an inquisitive but deeply considered work of drama. Harris’ doc, on the other hand, feels playful yet aimless, juxtaposing images with strong formal sensibilities but little direction.

The play’s rehearsals are all filmed, including long, unbroken takes of full scenes from the play performed by actors; sometimes they are single-camera monologues, other times dual-camera duets. Sometimes, these readings are edited side-by-side with other productions of the show, such as the Broadway run or its original staging at the Yale School of Drama. As Harris moves through the workshop, the film plays with fast editing, text superimposition, and other light flourishes. It’s all engaging, but to what end? Fans of the original play will be curious to compare performances and gain insight from Harris breaking down the play’s book and its unique meter. However, this novelty quickly wears off and it’s unclear what’s left to gain, especially in the context of its form as a film. This finally comes to a head in the film’s final third, which sees Harris editing the film with his editor and comparing cuts, including versions that feature him in an editing bay with his editor. The hall of mirrors effect is striking, but not as striking as Harris finally caving and revealing his true feelings: that film cannot ultimately capture the same raw intensity as theater and that the latter medium’s ancient origins prove its greater staying power.

This is a boldly enlightening moment – perhaps we’d put it under “saying the quiet part out loud” for a certain community of artists – but going through the effort of making a film to simply give in and accept film’s inferiority certainly doesn’t provide much of a resounding conclusion. If anything, it only asserts that no matter how many lines of your original play you read in front of a camera, you’ll never be able to fully channel the play’s raw power into the film’s bones. In that case, all you’re left with is process, and it’s simply too meager here to feel like its own unique beast. Theater fans, such as this critic, can admire the swing and find merit in the miss, but film fans will likely be left underwhelmed by the lack of substance.

Slave Play. Not a Movie. A Play. held its World Premiere as part of the Spotlight Documentary section of the 2024 Tribeca Festival. It is currently streaming on Max.

Jeremy O. Harris' process doc is a treat for theater fans looking to engage in 'Slave Play' with new faces, but finds little value in its grand experiment to reimagine the work on film.

-

User Ratings (0 Votes)

0

Larry Fried is a filmmaker, writer, and podcaster based in New Jersey. He is the host and creator of the podcast “My Favorite Movie is…,” a podcast dedicated to helping filmmakers make somebody’s next favorite movie. He is also the Visual Content Manager for Special Olympics New Jersey, an organization dedicated to competition and training opportunities for athletes with intellectual disabilities across the Garden State.