Socorro is a 67-year-old lawyer who hasn’t let go of the Tlatelolco massacre for nearly six decades, and when we meet her, she’s long past the point of reasonable obsession. The film isn’t really about “solving” a crime so much as watching what happens when someone’s identity becomes tethered to unfinished business that should’ve been resolved a lifetime ago. And from the first scenes, you feel the weight of that history sitting on her shoulders.

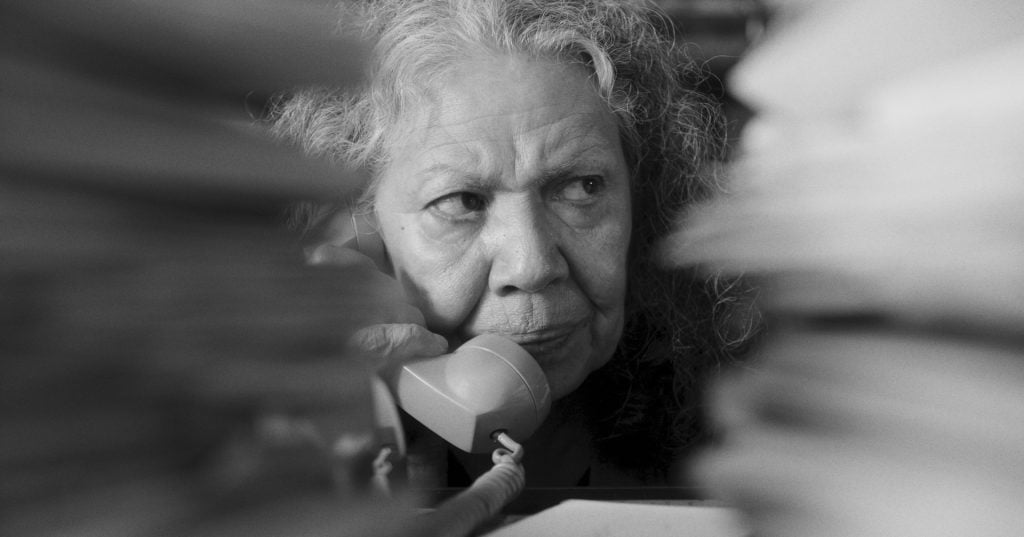

Luisa Huertas gives one of those performances where you don’t see the actor working, you just see a woman who has been living with the same ghost for fifty years. Every line she delivers carries a kind of dry exhaustion, like she doesn’t have time for anything that doesn’t point her toward the man she believes killed her brother. It’s a quiet performance, but the quiet doesn’t mean small. It’s the quiet that comes from someone who has repeated the same argument to herself for decades. Huertas completely locks you into Socorro’s head, even when her choices turn messy and irrational.

Saint-Martin shoots the film in black and white, and it fits the story in a way that never feels like a gimmick. The lack of color gives Socorro’s world a drained, fragile feeling, like the past has leeched everything out of the present. There were times when the cinematography felt almost tactile, especially in the interior scenes. The lighting is so carefully controlled that you can practically feel the texture of the furniture or the stale air in the room. It’s the kind of black-and-white that doesn’t try to be “pretty”; it tries to feel lived-in, and it succeeds.

The film also does something smart with sound. When Socorro’s memories of the massacre intrude, sometimes abruptly, Saint-Martin doesn’t turn them into melodramatic flashbacks. They’re more like intrusive thoughts. A sound from the present blends into a scream or gunshot from the past, and the cut is sharp enough that it genuinely throws you off. It’s unsettling, and it’s exactly what those moments should feel like. You understand immediately how deeply this trauma has attached itself to her, and why she can’t just move on because her family wishes she would.

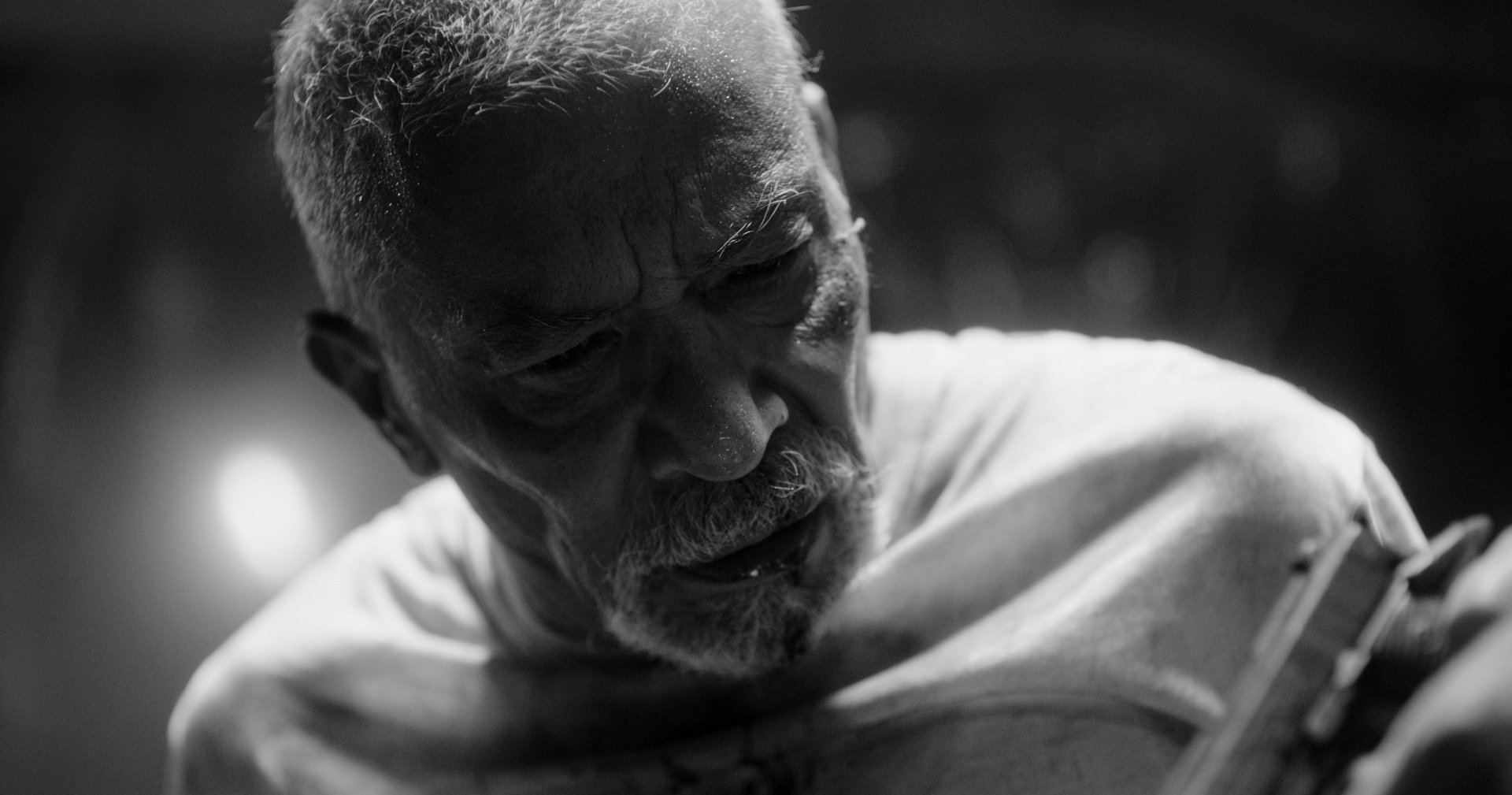

Speaking of family, one of the strengths of the film is how clearly the relationships are drawn. Esperanza, Socorro’s sister, feels like someone who has already mourned the same loss and accepted the fact that life has to keep going. Jorge, her son, is caught between wanting to protect his mother and wanting to detach from the burden of her mission. None of these characters feels like an accessory to Socorro; they’re fully realized people with their own exhaustion, frustration, and love. Rebeca Manríquez, in particular, brings a grounded warmth to Esperanza; her scenes with Huertas have a heaviness that feels real, like longtime arguments that keep looping back on themselves.

The movie also has a surprisingly sharp sense of humor that never undercuts the seriousness of the story. It’s not broad humor, it’s the kind you get when stubborn people insist on doing things their way. There are moments where Socorro’s determination becomes so exaggerated that it borders on the absurd, but Saint-Martin knows how to toe that line without turning the film into satire. The humor works because it comes from character, not from trying to “lighten the mood.”

Where the film stumbles, at least for me, is in the final stretch. Up until the last twenty minutes, everything feels like it’s clicking into place. We understand Socorro’s motivations, we understand how the past keeps leaking into her present, and we see how her pursuit is pulling her family apart. It almost feels like the film is shaping itself into a complete puzzle, one where the emotional and thematic pieces lock together. But then the ending arrives, and that last piece just… isn’t there.

It’s not that the ending is abrupt; it’s that it doesn’t feel earned. The build-up is strong, and the performances are doing everything they can to carry the weight of the story, but the resolution doesn’t land with the force the rest of the film has been promising. It leaves you with this feeling that the movie pulled back just when it should’ve pushed forward. Not in a “subverting expectations” way, but in a slightly undercooked way.

Still, even with the ending not quite landing, We Shall Not Be Moved has enough strengths to hold its ground. The character work is strong, the technical craftsmanship is clear, and Luisa Huertas is outstanding. Mexico chose it as their International Feature submission, and it was for sure the correct one. It’s a film rooted in a national wound, told through the eyes of a woman who represents a generation that never got closure.

It’s haunting, detailed, sometimes even funny in a surprisingly human way, and anchored by a performance in which she can carry the movie on her back. And even if that last puzzle piece is missing, the rest of the picture is strong enough to leave a mark.

We Shall Not Be Moved will debut at Cinema Village in New York City on November 28, 2025, courtesy of Cinema Tropical. The film will expand to additional markets in the near future. The film is Mexico’s official selection for Best International Feature at the 98th Academy Awards.

Even with the ending not quite landing, We Shall Not Be Moved has enough strengths to hold its ground. It’s a film rooted in a national wound, told through the eyes of a woman who represents a generation that never got closure.

-

8

-

User Ratings (0 Votes)

0

Roberto Tyler Ortiz is a movie and TV enthusiast with a love for literally any film. He is a writer for LoudAndClearReviews, and when he isn’t writing for them, he’s sharing his personal reviews and thoughts on Twitter, Instagram, and Letterboxd. As a member of the Austin Film Critics Association, Roberto is always ready to chat about the latest releases, dive deep into film discussions, or discover something new.