Is it better to be unseen or gawked at?

The question underlies every movement Edward, played by Sebastian Stan, makes in A Different Man. An aspiring actor with a facial deformity, Edward moves and speaks with the expectation that people are reacting to him in inherently negative ways: horror, disgust, pity, or plain old discomfort. The assumption is fair: his one acting gig is in a Human Resources video that teaches employees how to treat their disfigured colleagues with basic respect and decency. With condescension or worse lurking on the edges, you can understand why Edward would want to isolate and protect himself.

Meeting his new neighbor, aspiring playwright Ingrid (Renate Reinsve), undermines Edward’s self-preservation instincts. Edward and Ingrid become friends, but when something more romantic blooms between them, their mutual discomfort intercedes. Defeated, Edward undergoes a brutal experimental treatment that “cures” his deformity, leaving him with a conventionally handsome face. Edward fakes his death and becomes “Guy,” but he discovers his life has inspired Ingrid’s new off-Broadway play. Guy auditions for his part and gets it, using a “mask” of his old face. Guy finds himself in a twisted “art imitates life” mess, complicated by the arrival of Oswald (Adam Pearson), another disfigured actor who captures Ingrid’s attention and inspiration.

With A Different Man, director and writer Aaron Schimberg explores the intricate, contradictory, and messy realities of living with a disability. One reality is the absurdity of navigating space with people who don’t know how to engage or respond to you. The film’s pitch-black humor stems from the deep discomfort and awkwardness that Edward’s mere existence causes him and others. It manifests in varied, outrageous ways. Edward has to lean behind a man to grab his coat because they won’t budge. Another man slams into a restaurant window to harass Edward while out with Ingrid. There are enough foot-in-mouth moments to make you believe cringe is deadly. Each situation is beyond the pale, and Schimberg encourages laughter. However, it bears undercurrents of empathy, heartbreak, and personal reflection. Schimberg achieves this without framing Edward as pitiable or the butt of the joke. If anything, our hypocrisies and vanity are the punchline.

The film is more than punching up at our collective failings towards disabled people. Schimberg cracks open his three main characters – Edward, Ingrid, and Oswald – to see how they internalize those failings. Edward believes his appearance is the root cause of his crippling insecurity. When his disfigurement is “cured,” he posits his world will be better. On the surface, it is. Within hours of becoming Guy, he gets drunk with guys at the bar and hooks up with a girl in the bathroom. However, the Guy persona doesn’t overwrite his experiences as Edward. He may look like a Marvel actor, but he is still uncomfortable in his own skin and can only approximate the confidence of someone conventionally handsome.

Guy’s performance deteriorates when he learns about Ingrid’s play. Throughout rehearsals and their relationship, it becomes clear that Ingrid never regarded Edward as either a love interest or friend. Ingrid uses Edward’s emotional struggles with his disability as creative fuel, unintentionally but cruelly forcing Guy to confront her musings about his condition for the sake of art. When he pushes back, Ingrid ignores him, only seeing Guy as an actor and not caring about Edward’s truth. The cognitive dissonance only worsens with Oswald’s presence. Oswald is everything Edward thought he couldn’t be due to his appearance: friendly, confident, and ruthlessly charismatic. In the film’s most heartbreaking scene, Oswald sings karaoke, and Guy observes him and the audience, who are captivated not by his condition but by his sparkling personality. Ingrid fetishizes Oswald as she did Edward, but his self-esteem inures him from Guy’s emotional devastation.

The tension between Guy’s deep-seated insecurities from his life as Edward, Ingrid’s narcissistic disregard for Edward’s life, and Oswald’s dazzling self-assuredness eventually pushes Guy to the brink. Schimberg takes some colossal swings in demonstrating that breakdown, and while he charts a compelling path, the destination isn’t as sound as the journey. The film’s final stretch adds little to how we perceive Guy’s dwindling emotional state, either repeating key points about ironic art or pushing him towards choices that lack the nuance of what came before. The final scene puts a somewhat neat bow on Guy’s story, but Schimberg communicates the point more elegantly elsewhere. The film effectively runs out of perspective, as if the camera was left on the characters longer than intended.

Considering the three central performances, the impulse to stay with A Different Man’s characters is forgivable. Renate Reinsve is excellent as Ingrid, a reprehensible character who perfectly encapsulates the worst of “main character syndrome.” She makes us hate Ingrid for her selfishness and cruelty but keeps us engaged with a potent, self-possessed allure. Adam Pearson is a firecracker, illuminating the film’s dark edges with sparkling wit and sensitivity that is impossible to resist. His chemistry with Reinsve and Sebastian Stan pushes them to greater heights, sharpening their characters’ respective best and worst tendencies. Pearson may be one of the year’s most captivating scene stealers.

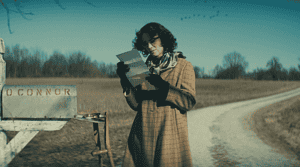

As for the titular man, Stan essentially plays two characters: Edward while in makeup and Guy without it. The pseudo-dual roles require significant physical skill to link them, and Stan demonstrates his skill brilliantly. As Edward, Stan moves with subtle, unwieldy discomfort, conveying hesitance and regret in how he takes up space. He carries that over as Guy, layering his uniquely unsettling, powder-keg charisma over Edward’s tentative ungainliness. What unifies the two is the crippling insecurity Stan conveys through his eyes, especially in silence. He shows, with laser-like precision, how Edward’s self-hatred eats away at his insides, causing him excruciating pain until it hollows him out. Edward and Guy are an amalgamation of Stan’s strengths as an actor and are his best performances to date.

A Different Man is an ambitious, thought-provoking film about how society treats disabled people, even under the cover of modern enlightenment. The film shows us how exploitation and condescension are easy to fall back on. It also shows how the most emotionally vulnerable, like Edward, can internalize that treatment. With dark humor, psychodrama, ethical commentary, and body horror, Schimberg raises a mirror, asking difficult but worthwhile questions about how inclusive we’ve become. Given how close to home Edward’s instructional HR video hits, we have a long way to go before people can live without debating if being unseen or gawked at is the better choice.

A Different Man will have its New York Premiere as the opening night film at New Directors/New Films 2024. It will be released on a date yet to be determined courtesy of A24.

Director: Aaron Schimberg

Screenwriter: Aaron Schimberg

Rated: NR

Runtime: 112m

A Different Man is an ambitious, thought-provoking film about how society treats disabled people, even under the cover of modern enlightenment.

-

GVN Rating 8.5

-

User Ratings (0 Votes)

0

A late-stage millennial lover of most things related to pop culture. Becomes irrationally irritated by Oscar predictions that don’t come true.