With Brett Morgen’s documentary Moonage Daydream (2022) hitting cinemas, it seems only fitting to slip into David Bowie-spotlight mode. Morgan’s documentary offers a career-spanning look at Bowie’s singular presence and influence on music and pop culture. Bowie’s uniformly superb appearances in movies across his career are within that legacy. Bowie’s acting career properly launched with The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). The Thin White Duke went on to work with the likes of Tony Scott, David Lynch, and Martin Scorsese. Arguably though, one director and one film understood Bowie’s distinctive allure clearer than any else. That would be Jim Henson and Labyrinth (1986), where Bowie transformed into Jareth the Goblin King.

During the mid-1980s, Bowie and Henson both enjoyed the broadest commercial success of their careers. Bowie recorded “Under Pressure” with Queen in 1981, and his 1983 album Let’s Dance remains his best-selling release. The burgeoning MTV era also catered to the cinephilic Bowie who ripped off a string of sexy videos including a winking From Here to Eternity nod in “China Girl.” Similarly, after a stretch defined by children’s television programs like Sesame Street and The Muppets, Henson pivoted to adult fare with SNL sketches and contributions to The Empire Strikes Back (1980). He also took the Muppets to the big screen with the massive hit The Great Muppet Caper (1981). His follow-up The Dark Crystal (1982) was not as big a financial hit but earned him critical raves and suggested a future in fantasy.

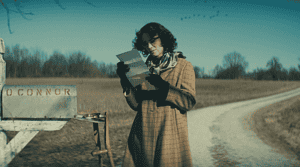

Those career strands merged for Labyrinth. The film focuses on teen Sarah (Jennifer Connelly) who offhandedly wishes her baby brother Toby (Toby Froud) would disappear. Shockingly, Jareth grants her wish and whisks Toby away. Sarah has thirteen hours to navigate his labyrinth before Jareth keeps Toby forever. In Henson’s vision, the labyrinth was primarily populated by puppets. The only human performers are Connely and Bowie, with baby appearances from Froud more as a prop than performance. Connelly’s Sarah is a classical coming-of-age figure. A teenager who wants to have fun instead of taking on the responsibility of caring for this crying baby. Bowie’s Jareth is her thematic foil in every way. Speaking with L’Écran Fantastique at the time, Henson noted that he cast Bowie because he “embodie[d] a certain maturity, with his sexuality, his disturbing aspect, all sorts of things that characterize the adult world.”

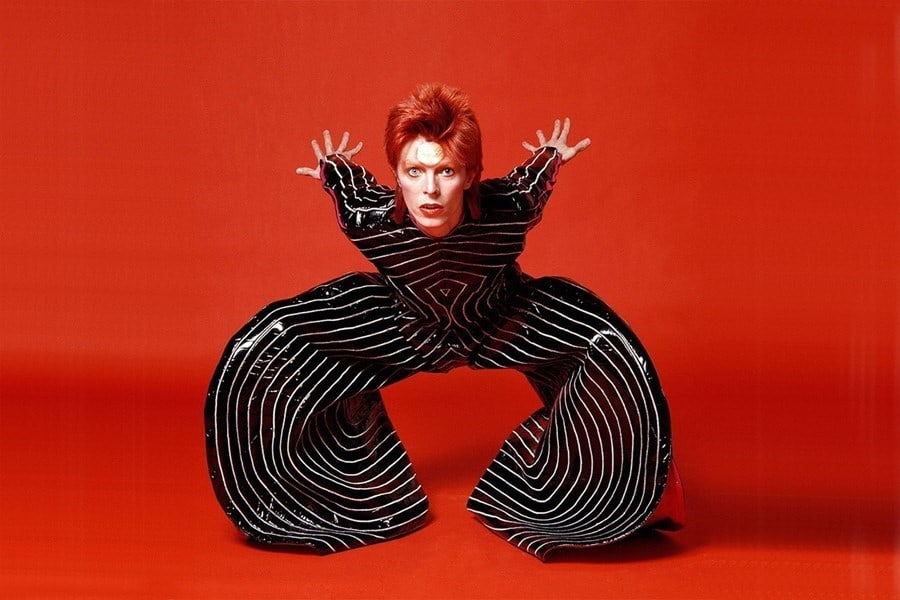

Simply looking at Jareth you can understand what Henson meant. By 1986, Bowie had already cycled through sensational personas. From Ziggy Stardust to Aladdin Sane, Bowie manifested colorful, gender-blurring, and erotic visions of his rockstar life. Jareth fits snugly into that arc. A carnal figure done up with mostly black tight pants, frills, and make-up. An enviable, sweeping, blonde updo. Set opposite Connely’s dominantly white costuming, the duo is a study in aesthetic opposition. Henson’s goal of Bowie/Jareth as a vessel of the “adult world” means that the actualization of the dynamic is a seductive evil. His essence draws both Sarah and the audience to Jareth’s devious tempting. As Alison Stine wrote of her own childhood experience with Jareth, “I was drawn to the danger in him. I felt the pull of the magical world he promised.”

Adding to Jareth’s inherent allure is that all of the goblins he rules over are repulsive. Stunted creatures with bulging eyes, green mottled skin, and all manner of warts and wrinkles. In that way, they are far more in line with the traditional envisioning of the creatures than Jareth. In his 1872 book The Princess and the Goblin, George MacDonald describes the creatures as “not ordinarily ugly, but either absolutely hideous, or ludicrously grotesque both in face and form.” While hardly the first to ascribe such visages to goblins, MacDonald’s words embody the viewpoint on goblins passed down through centuries of mythology and folklore. Therefore, sculpting Jareth in the pop cultural image of a bewitching Bowie and offsetting him with these gnarled lackeys elevates his every bawdy motion. For Sarah and any of us watching, Bowie’s image is an island of appeal amidst a sea of brutes.

Nowhere is this weaponized more than when Bowie starts singing. Labyrinth features five songs performed by Bowie, as well as a sixth that he wrote but did not sing. Of the five, two of those roll out in iconic scenes that function as showcases for the breadth of Bowie’s ability to enchant. First comes “Magic Dance,” an earworm of a dance number Bowie sings while, you guessed it, dancing around his throne room. The first notes hit as Toby sits on the floor crying, surrounded by salivating goblins. Bowie lounges suggestively on his throne holding and flicking a riding crop. It centers his restless energy and nods at the constant eroticism, but all that fades as he bursts up to sing. Laughing broadly and strutting around, Bowie plays “Magic Dance” as much as a comic showpiece as a pop lullaby to quell the crying Toby. He is magnetic.

That energy modulates in a masquerade ballroom sequence that I can only imagine Stanley Kubrick watched incessantly before making Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Sarah arrives in her illustrious white ballgown and searches for Jareth. He glides through the revelers until he pulls her into a dance. Layered over Henson’s dreamy cross-dissolves and slinking camera, Bowie sings “As the World Falls Down,” a synth-heavy ballad that Bowie intones with a breathy and throbbing singing voice. In terms of plot, it is understood to be a dream, a challenge for Sarah to face. Yet, even as we logically shiver at Jareth’s moves towards Sarah, his presentation challenges all reason and good judgment. Yes, the music is dated by today’s sonic standards, but the sequence remains a sensual lightning bolt. We come away disgusted that we have been entranced, but unable to deny Jareth’s power.

Labyrinth was not the first time Bowie played a ravishing monster. He delivered astounding work in Tony Scott’s criminally under-appreciated vampire masterpiece The Hunger (1983), but Labyrinth is the first, and arguably only, film to capitalize on every facet Bowie brings to the screen. He undulates, sings, winks, and snarls his way through every scene. Jareth is the undeniable antagonist. Yet, Bowie and Henson ensure that his intoxicating power infects us as much as it does Sarah. Returning to Stine, she writes that “Just as I never understood why Dorothy Gale left the wonderful world of Oz and returned to flat, hot Kansas, I didn’t understand why Sarah went back from the Goblin City, to be a babysitter, an ordinary teenager.” Stine goes on to make clear that it is necessary for Sarah to return, but that impulse we all share as viewers speaks to Jareth’s dominance.

There have been few figures quite like David Bowie, and Moonage Daydream is the latest in a series of reckonings with that fact since Bowie’s death in 2016. As you look around, there is no shortage of ways to dive into Bowie’s significant body of musical, filmic, and other work, but Labyrinth stands apart as an example of a role and cinematic vision engineered to best deploy him. Turning it on thirty-six years later, it is only too easy to slip back under his spell.

Devin McGrath-Conwell holds a B.A. in Film / English from Middlebury College and is currently pursuing an MFA in Screenwriting from Emerson College. His obsessions include all things horror, David Lynch, the darkest of satires, and Billy Joel. Devin’s writing has also appeared in publications such as Filmhounds Magazine, Film Cred, Horror Homeroom, and Cinema Scholars.