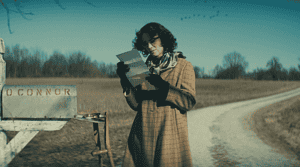

Few films at the 2024 SXSW Film & TV Festival lead with a stronger hook than Dead Mail. In the film’s opening moments, an unassuming suburban house has its door burst open by a black man (Sterling Macer, Jr.) crawling for dear life. His hands are attached to a chain, his legs are bound together with rope. His mission: to deliver a torn piece of paper to the street’s mailbox so that he may find some semblance of escape. He is successful, but at a cost. His captor, a lanky white man (John Fleck), frantically comes running for him and incapacitates him. What now?

This is the central question that drives the remaining hour and forty-five minutes, and viewers who think the answer is straightforward will be quickly proven wrong. Hidden underneath the headliners and spotlight sections as part of South By’s always-compelling “Visions” section, Dead Mail begins as a mystery brought upon a humble post office worker in the Midwest. However, it quickly unravels as a treacherous story following a humble synthesizer engineer and his passionate, if treacherous, business partner.

Utilizing the same unpolished aesthetics of high stakes but lo-fi 70s horror-thrillers like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes, Dead Mail tells an emotionally charged story of perseverance and obsession. Anchored by two powerful lead performances from Macer and Fleck, the story will rope viewers in with its unique premise and strong sonic identity only to then throw them for a loop as the descent into violence spirals further and further.

Geek Vibes Nation had the chance to speak to Macer, Fleck, and Dead Mail co-directors and co-writers Kyle McConaghy and Joe DeBoer ahead of their world premiere in Austin, Texas about their creative process, including how the power of music is interwoven into the film’s suspenseful drama. Here is our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Where did the idea for Dead Mail come from?

Kyle McConaghy: I don’t know if he was reading National Geographic or World Book Encyclopedia or something, but Joe discovered this real-life dead letter office in the postal service where they investigate undeliverable mail that has value. He was like, “Hey, I think this could be maybe a concept for a film.”

Joe DeBoer: I don’t remember this story but I’ll take the credit. [laughs]

Kyle McConaghy: We developed the first scene of Dead Mail where our character, Josh, is bound and delivering this letter. From there, we wanted to follow the trajectory of the letter. We know we’ve got this sensationalized investigative first act, but what could we have Josh do? It led us to an analogue synthesizer engineer and some other things we were hoping to cover in a film and it snowballed from there.

Focusing on synthesizer and synthesizer construction is a very interesting, niche place to go.

DeBoer: That was rooted in our upbringing and musical artists that we really loved and respected. Wendy Carlos [was a] big influence. We had a couple analogue synths and, when we used to collaborate more musically, we’d occasionally pop them open. Kyle would get in and maybe play with a circuit and, “Oh, we got a note to work that didn’t work before!” It was kind of a personal thing.

McConaghy: Sterling unlocked something earlier today when was he was talking about how Josh’s character is consumed with wanting to create these specific, beautiful sounds. When Joe and I have written music, that was almost as important as the melody, the actual texture and sonic quality. We loved old analogue sounds, but in the early 2000s or whenever, it was hard to find that. The only way you could get that was through old synths, so we had to go on eBay and buy these half-broken synths and try to make them work.

Sterling and John, something I noticed is that the writing is filled with beautiful, verbose language. The way the characters speak to each other is really special for a film that’s as pulpy as this one is. What were your reactions to first seeing the script?

Sterling Macer, Jr.: It’s funny because this comes up not just in interviews but generally is bandied about, our appreciation for the words these guys get on the page. They’re words that actors like to speak because it’s not the typical syntax. It’s a lot of figurative language that you can lean into. It leaves the actor with room for interpretation. It’s the nature of what we do to traffic in the subtext, so it leaves room for and allows you to say normally straightforward things in a much more circuitous way. It’s a joy. Having worked with these guys before, that’s one of the things that really draws me to their work.

Circuitous feels like a word that would be in this script. [laughs]

John Fleck: The first thing that comes into my mind was this tin drum image that was in [a monologue in] the script. I really related to that. Living in a tin drum with just two little slits. There’s a chance to open it up and finally come out and then, grr, clamp. I just love the whole arc of [my character]. “I’m feeling alive again. I’m hearing sounds that we’re working on, this purity, this relationship, and I found a loyal partner.”

McConaghy: A quick aside to the oil drum––a pretty close version of that speech was delivered to Joe and I when we were in 11th grade social studies. [all laugh]

Fleck: Really?

McConaghy: Our teacher, poor guy, had some mental issues and he had to leave for a couple months. He came back and you could tell he was still not doing well. He delivered a speech about being in an oil drum—

Fleck: love that connection.

McConaghy: …and he could see the world but the world couldn’t see him. We were like, ‘We’re going to have to use that.’

Fleck: Wow.

John, you touched on this beautiful, twisted relationship. How are you two, as actors, working together to plot out and convey the way the partnership develops?

Fleck: We work really well together. In terms of the plotting, for me, these guys [Kyle and Joe] guided me in terms of where it’s going. It starts off in kind of a bing, a spark of a kindred soul. You shoot out of context, so you really have to have the puzzle pieces.

Macer: It’s a great question because the nature of your question is about the arc, right? How do you lay that out? There’s a dichotomy involved with it because your job as an actor is to dive into the character and hopefully have an empathetic connection such that everything that you’re doing is truly organic. At the same time, there’s a craft notion to it, too. You don’t want to repeat beats over and over, so you have to depend on the direction to let you know that, “Hey, you’re painting blue here but save that blue for this over here because you’re going to need it later on.” So, you have to find a different way to come at that same vibe. It’s about understanding the color palette of the arc, trusting the directors to help you navigate it, and then letting the characters still live in an organic, natural, real way.

Speaking of direction, let’s talk about that. The aesthetic is like a time capsule. I felt like I had been brought back to an era of Texas Chainsaw Massacre and films that felt really on-the-ground, unpolished. I feel like a lot of films try to replicate that era but cannot overcome the modern, industry-standard technology they have to use to achieve it. Can you break down how you achieved the look and the sound of the film?

DeBoer: In general, we’re drawn to things that have a lot of texture to it. When you listen to Joy Division’s music, you feel like you’re in that Manchester, UK warehouse where they recorded it. Texas Chainsaw Massacre has always been a reference for us.

McConaghy: Yeah.

DeBoer: It’s not just the film grain but you could feel the film on you. I think we wanted to capture some of that, to a degree. We’ve tried to develop retro looks before to varying degrees of success. For this one, we knew we had this drab, authentic Midwest we want to capture that we remember from our youth. We said, “Let’s do what we can to achieve some version of that.” At the same time, we didn’t want to be too derivative of something specific in the film space. Obviously, many films have influenced this film, but pertinent influences we were looking at were Janet Delaney and Jamel Shabazz, who were photographers in the 80s, and memories of VHS family-friendly videos we’d watch as kids. Family photos came into play, for sure. Technically though, we couldn’t afford to shoot on film, so we shot on the RED KOMODO. We used these old ZEISS lenses, B-speeds from the 70s and put some filtration on it, but a lot of it was also done in post when we worked on the color grade.

McConaghy: Utilizing harder practical lights was a really important key. Then, it was about making sure the sets felt authentically like the Midwestern backdrops we would see in photos, as opposed to the Hollywood glamorized version of the 80s with the neon and stuff like that.

DeBoer: More The Brood, less Back to the Future. [all laugh]

You were speaking about how you were dabbling musicians before you became filmmakers. In a twisted way, this film is about the power of music and how that affects people to varying degrees. I was wondering if you could all speak to that theme in the film and what it was like to tell a story where music is so deeply weaved into it.

DeBoer: Janet Beat was the first synth engineer that Kyle actually discovered that does the tinkering music. I think, in post, that really set the tone for us. We said, “Let’s use the diegetic music throughout. Let’s really let the synth drive it,” and it was all completely motivated. We’ve got the synth engineer. Some of the opera tracks [in the film] felt so contradictory to what we were viewing. There’s such an ability for music to manipulate the feeling of something. So, once we started to untap that, it just opened wide what we could do tonally.

Macer: All art is basically tension and release. It’s just a matter of how you get there. To be able to be in a film that is using something as unique as synthetic sound to aid in the journey of that is really special. It’s how I process how the sound and the score relate to that storytelling experience for me as an actor.

McConaghy: There’s a magic to music. It doesn’t make sense why it resonates with us emotionally so much when it’s an art form that you can’t see or touch. We sifted through dozens and dozens of classical tracks [for the soundtrack] knowing that Josh was probably going to listen to classical composers that are readily available, not too deep of cuts. Then, one would pop up and like, “Alright, that’s it. That’s definitely the one.” It was fun to be able to use that diegetic music for this.

Fleck: I was developed in the 80s as a performance artist in New York on stage. Klaus Nomi, the countertenor, was a big influence on me. When I watched the film last week, I heard “The Cold Song” by Henry Purcell, and that was one of my signature songs I used to perform in New York.

McConaghy: Oh, no way! Of course you did.

Fleck: [singing] Oh, what pow-ow-ow-er art thou-ou-ou, who from-om-om below-ow-ow hast made-ade-ade me rise-ise-ise! That’s what I used to sing all the time.

DeBoer: That became your theme!

Fleck: Well, yes!

McConaghy: Wow, that’s really weird.

Fleck: Yes and “Dido’s Lament.” When I first read the script, that was a synchronicity. I was like, “Okay, this is meant to happen.”

DeBoer: He sang “Dido’s Lament” for us in his audition and it took us 30 seconds afterward to be like, “This guy needs to be Trent.”

McConaghy: He doesn’t need to read for the role.

Fleck: We can turn this into an opera if it ever gets there.

Dead Mail held its World Premiere as part of the Visions section of the 2024 SXSW Film & TV Festival. It is currently seeking distribution.

Larry Fried is a filmmaker, writer, and podcaster based in New Jersey. He is the host and creator of the podcast “My Favorite Movie is…,” a podcast dedicated to helping filmmakers make somebody’s next favorite movie. He is also the Visual Content Manager for Special Olympics New Jersey, an organization dedicated to competition and training opportunities for athletes with intellectual disabilities across the Garden State.