I am old enough to have enjoyed the waning glory days of movie rental spots. My southern Maine hometown had a Movie Gallery. Anytime my parents took me down to pick something out it was a glorious day. They had a closeout sale when doom was inevitable. I still have a handful of DVDs from that sale on the shelf a few yards from where I’m writing this review. My parents have the same back home. In a pre-streaming world, those rental shops were palaces of cinema—an avenue for discovery and connection. They were also a tangible way to know you had access to titles, something that has come back to prominence in the era of streaming services disappearing titles for tax breaks. Their particular vein of power is what motivates Ashley Sabin and David Redmon’s documentary Kim’s Video (2023).

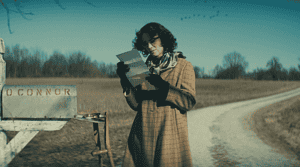

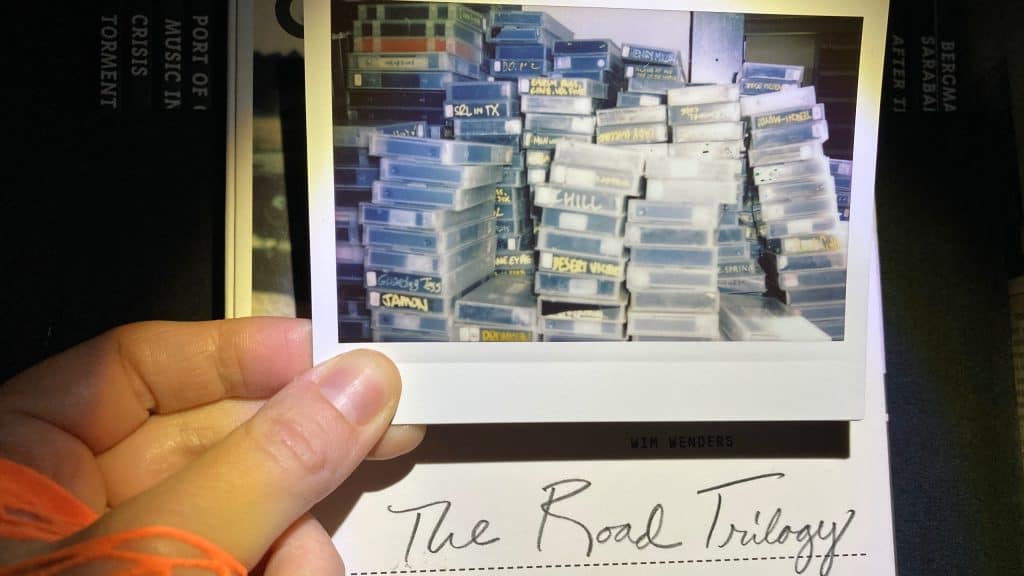

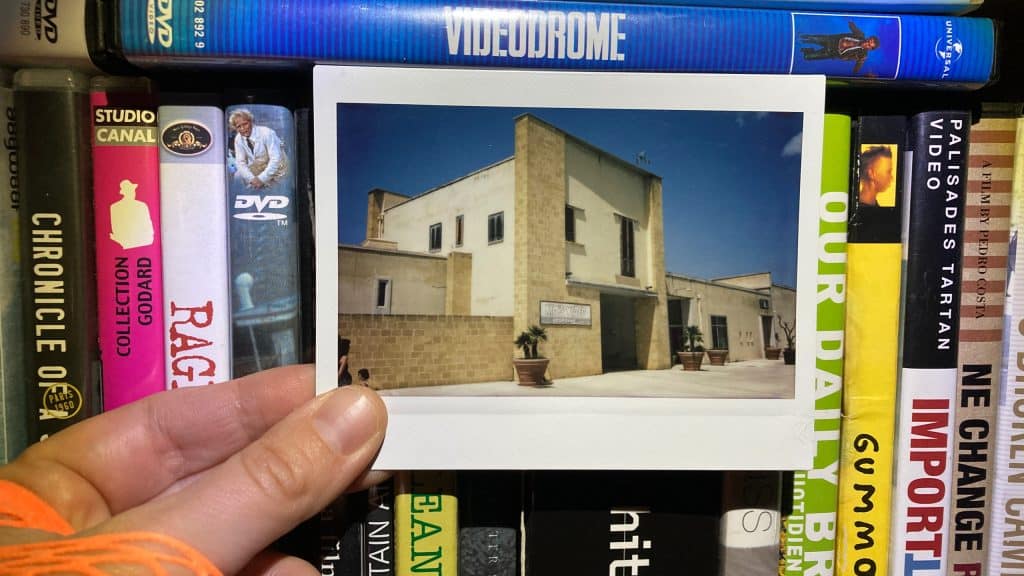

Businessman and all-around enigma Yongman Kim opened his first video store in New York City in 1987. Over time, that expanded to five other locations in the city. At its peak, the network had over 55,000 rare titles at its disposal. Then streaming happened. The last Kim’s location closed in 2008. Mr. Kim proposed donating the entire collection to a worthy place or organization. Through an opaque turn of events, that place turned out to be the small village of Salemi, Italy. Time passed. The pomp of the initial Salemi move dissipated, leaving many former Kim’s customers wondering what happened to the collection. Enter David Redmon. Armed with a basic filming rig and tidbits of information, Redmon undertook the quest to discover the collection’s status with the hope of recovering it. His journey from New York to Italy and beyond became Kim’s Video.

The opening stages of Kim’s Video reminded me of Searching for Sugar Man (2012), another documentary fixed on excavating a forgotten part of art history. Redmon puts Kim’s Video in the cultural context of the East Village where it started. Flashes of news and short interview snippets establish the impact that Kim’s Video had on its customers and former employees. It has an on-the-ground quality with Redmon’s handheld camerawork and narration but is otherwise a rather straightforward documentary. That changes the moment Redmon lands in Salemi. A hilarious stretch where he encounters a series of older Italian men who speak no English feels only a few bits removed from After Hours (1985). When Redmon does finally make it to the Kim’s Video archive in Salemi, it sets off a series of increasingly absurd wrinkles that uncover the truly bonkers truth about the collection’s status.

Redmon’s camerawork, paired with his and Sabin’s editing choices, morph and mutate to meet every curveball. What starts aesthetically as a video essay-history vlog hybrid starts to resemble Man With a Movie Camera (1929) in Italy. As Redmon uncovers political intrigue and possible mafia ties, the pacing ratchets up into the true crime docu-drama range, complete with a prosecutor silently walking down the halls of justice. Things get starkly experimental as we barrel towards a rather jaw-dropping turn of events that constitute the story’s climax (I couldn’t possibly spoil the joy of discovering exactly what that is for yourselves). All the while, Redmon’s soothing voice, and first-person camerawork ground us in his very real and human task at hand. There are moments when the choice to feature so many clips of movies to make connections between life and art feel cumbersome. That is only a minor quibble.

Kim’s Video is as much about the quest at hand as it is thematically about personal relationships to art, and how the fight to preserve art is often a revolutionary act. There are a series of images from Kim’s Video that will stay in my head for a while, but the moment that Mr. Kim himself visits the collection in Salemi and finds much of it dusty and water-logged is a potent one. He is not a man who seems prone to dramatics, and his outward reaction is now broad. Yet, in his just-watery eyes and tensed demeanor, we see a man confronted with what is both his greatest achievement and possible failure. Mr. Kim devoted years to curating the 55,000 titles, and the powers that be in Salemi did not honor that devotion while Mr. Kim pulled back himself. It is searing stuff.

The Kim’s Video arc thankfully bends toward relative justice by the end, as anyone reading the news now knows that the collection has found a loving home back in New York City at Alamo Drafthouse. But, that fact is, oddly enough, rather perfunctory to the experience of watching Kim’s Video. In this case, as it is many, the journey is the point, and oh my what a journey Kim’s Video takes us on.

Kim’s Video had its World Premiere in the NEXT section of the 2023 Sundance Film Festival.

Director: Ashley Sabin and David Redmon

Rated: NR

Runtime: 88m

'Kim's Video' is a zany and charming documentary about cinematic legacy

-

GVN Rating 8.5

-

User Ratings (0 Votes)

0

Devin McGrath-Conwell holds a B.A. in Film / English from Middlebury College and is currently pursuing an MFA in Screenwriting from Emerson College. His obsessions include all things horror, David Lynch, the darkest of satires, and Billy Joel. Devin’s writing has also appeared in publications such as Filmhounds Magazine, Film Cred, Horror Homeroom, and Cinema Scholars.