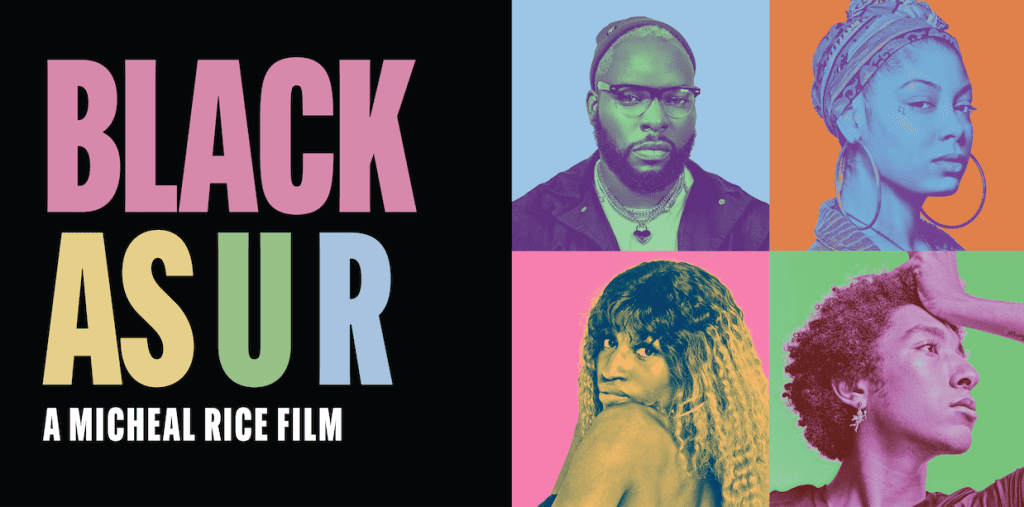

When a clip of your latest film gets spread around social media, it can sometimes spell disaster. For Micheal Rice, director of BLACK AS U R, it spelled something even more unexpected.

“People were calling me saying, ‘Billy Porter just posted a clip of your film on his page.’ I was like, ‘What? Are you serious?’ They were like, ‘Yeah.’”

The original post now sits at over 7,000 likes on Instagram. It didn’t take long for Porter’s representation to reach out. “[He] loved the film so much that he just signed on as an executive producer,” confirms Rice.

“I think this will be the first interview where I can talk about it.” At the time of recording, the film had made its premiere at NewFest, New York City’s premiere queer film festival, mere days earlier. “I think the paperwork was signed, like, two days ago.”

It is a major victory of visibility for BLACK AS U R, a documentary that sheds light on the ingrained homophobia and transphobia within Black communities. For Porter, one of the entertainment industry’s most visible queer and black artists, to champion the film is to further push this population, and its adversity, into the spotlight.

“It’s kind of like lifting the rug up and sweeping out the dirt,” says Rice. “[It’s] not necessarily a hot topic that people want to have a conversation about. We’re so on the frontlines, constantly fighting just for human rights, that sometimes things that are more complex, like, ‘What is it like to be LGBTQ and Black’ and ‘What do those conversations look like with our families,’ may not be at the forefront.”

By interrogating communities of color, as well as interviewing a variety of trans and genderfluid creatives, Rice exposes how heteronormative hyper-masculinity imposes oppressive systems of power against a population in which he, himself, is a proud member. “It was incredibly important for me, as a Black, gay filmmaker, to create something that is authentically coming from the spirit of a Black, gay creator.”

For those who do not often interact within these communities, the results are eye-opening. In fact, that has been a majority of the film’s audience. “In touring this documentary, most of [the screenings] have been heavily White with few people of color,” notes Rice. “But one thing I realized is that [the film] deals with subject matter that we all deal with: patriarchy, White supremacy, bigotry, ignorance. That’s a lot of stuff that we all, as a human race, can understand, but you’re just looking at it through another lens.”

GVN spoke to Rice about a number of powerful sequences in the film, what it means to have Porter on as an executive producer, and the universality in the film’s dissection of religious communities. Here is that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

–

Larry Fried: Micheal, congratulations on the success of BLACK AS U R. It has played at numerous festivals and received a substantial amount of recognition at NewFest, including the Documentary Feature Audience Award, the Chevrolet Changemaker Award, and a special mention by the Documentary Jury. How are you feeling now that the film has been seen by so many audiences and has been getting so much recognition?

Micheal Rice: I’m elated, I’m overjoyed. As an artist, you put a lot of work into something. I’m really cool with people just recognizing it. But then, on top of that, for jurors and also audiences to actually vote because they were impassioned by the film is just an incredible honor. I’m taking it one day at a time. We also have some really great things that are happening behind the scenes. I think this will be the first interview where I can talk it––the good news is that Billy Porter loved the film so much that he has just signed on as executive producer.

Fried: That’s amazing!

Rice: Yeah. I think it was incredibly gracious for Billy to not only say that he loved the film but post the film on his Instagram. I got a flurry of likes and thousands of hits. All of a sudden, people called me saying, “Billy Porter just posted a clip of your film on his page.” I was like, “What? Are you serious?” They’re like, “Yeah.” Two weeks later, one of his people reached out. My agent and my publicist got involved and we made a situation happen. It just literally happened. I think the paperwork was signed, like, two days ago.

Fried: That’s very, very exciting. Was there a fear that the film wouldn’t be embraced as much as it has?

Rice: Internally, I knew there was a possibility. It’s kind of like lifting the rug up and sweeping out the dirt. We talk about aspects of queerphobia and homophobia in the Black community and what that looks like and that’s not necessarily a hot topic that people want to have a conversation about. It may expose people’s bigotry or ignorance or lack of wanting to understand what’s going on. At the same time, too, it also creates a space for LGBT people of color, particularly Black LGBT people of color, to have these conversations with their families and to understand aspects of talking about transphobia. These kinds of conversations are not necessarily at the forefront of our community, particularly the Black community.

Rice: Internally, I knew there was a possibility. It’s kind of like lifting the rug up and sweeping out the dirt. We talk about aspects of queerphobia and homophobia in the Black community and what that looks like and that’s not necessarily a hot topic that people want to have a conversation about. It may expose people’s bigotry or ignorance or lack of wanting to understand what’s going on. At the same time, too, it also creates a space for LGBT people of color, particularly Black LGBT people of color, to have these conversations with their families and to understand aspects of talking about transphobia. These kinds of conversations are not necessarily at the forefront of our community, particularly the Black community.

I just feel like we’re so on the frontlines of constantly fighting just for human rights that sometimes, things that are more complex like, “What is it like to be LGBTQ and Black?” and “What do those conversations look like with our families?” may not be at the forefront. What I’m doing with BLACK AS U R is putting those difficult or complex conversations at the forefront so we can at least create a space where we can have open dialogue. To me, that’s a good start.

Fried: Speaking of open dialogue, I want to jump right in and talk about one of my favorite sequences in the film, which is the scene that takes place in the barbershop. It felt like you were bringing the very nuances of the complexities of this conversation to the forefront, as you described. What was it like to shoot that scene in that kind of environment? Was there trepidation in entering that space with the purposes of being a documentarian?

Rice: Yeah, on a couple different planes. On the first plane, being a Black queer child that was trying to understand who they were and understand what “queer” or “LGBT” even was, I always had a fear of being outed in the barbershop. It’s a social place where, a lot of times, Black folks feel safe and they get the scoop on what’s happening in the community and there’s a form of support. But because a barbershop has a high level of masculinity, I’ve always had that fear of being outed there. That was as a child, but the fear hasn’t actually left, even as an adult in my late 30s. When it was time for me to shoot this scene, I was a little perplexed because it was almost like facing your fear. I sat in my uncomfortableness so I can hopefully create a space for somebody else to be more comfortable to talk about issues of LGBT-anything within an environment like that. It was a challenge.

As a producer, I’m very organized and planned but, with this particular scene, we literally had to shoot on the spot. The barber didn’t mind us having this conversation, but he didn’t have time to select people to be in the barbershop. He told us a very specific time to be there and I had a team of, like, three cameras and a production assistant. We didn’t know the people who were going to sit in the chairs were actually going to be there. Everything that you actually saw––how the camera was moving, how we were trying to make room for one another––it was totally organic and it was one of the highlights of the film.

Fried: When you make a documentary, it really does feel like, more often than not, you’re finding it as you go along. BLACK AS U R deals with topics that are so modern and timely and in-our-faces at this very moment that it really felt like it was responding to things in real time. Would you say that was what the process was like?

Rice: It really did happen in real-time. Literally months away from when these events actually happened, I started getting a camera and my team and we started recording. I originally created a play for Pride Month called There’s Black in the Rainbow Too. It dealt with the same subject matter of confronting homophobia in the Black community. My play rehearsals got shut down because of COVID, so I decided, “Okay, maybe I should do a documentary and move around on my own and use narration to still tell the story.”

What really ignited it as a documentary for me was seeing images of Black bodies constantly being shot and killed during COVID. It was trauma porn happening every day sitting in front of the TV. It was Breonna Taylor, it was Ahmaud Arbery, it was then George Floyd, and I began to protest on the street. Then, all of a sudden, we saw the brutal beating of Iyanna Dior and I became enraged because it was my own people. Not to say that we’re a monolith, but it was my own people that were literally miles down the road from George Floyd’s vigil that were beating on this 19-year-old trans girl.

I spoke out about it on social media and I thought I would get a huge amount of support, but I actually got a lot of hate mail and [people saying] ‘Why are you defending this? You’re distracting from the Black Lives Matter movement to talk about LGBT issues.’ As if Black LGBT people could not be a part of both communities at the same time. It was almost like you had to choose one or the other. So, I decided to do something about it and move forward with the documentary.

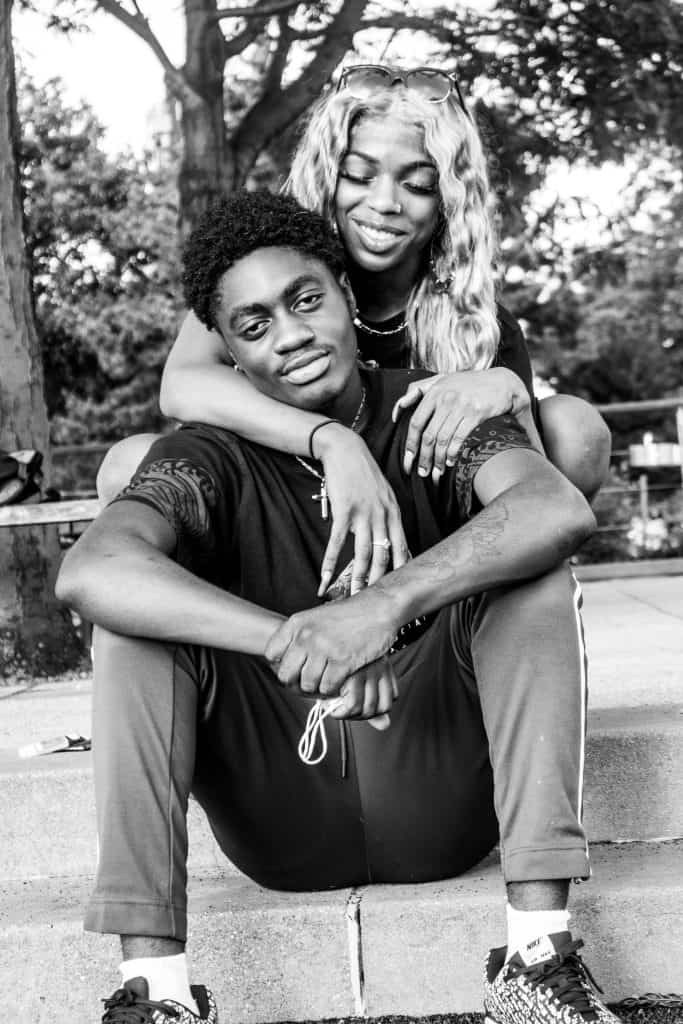

Fried: Toward the middle of the film, you follow this group of dancers and they become a major centerpiece in the documentary. Then, you cut to later where we find out that one of them is missing. Talk to me a little bit about meeting them and then incorporating this ongoing, real-time situation.

Rice: When I came to New York City at 21 years old with a few thousand dollars in my pocket, I asked around: “Where is the gay scene? Where are all the gay people hanging out?” Someone told me, “Go to the West Village, go to Christopher Street, and you’ll see it,” so I always knew where the gay community socialized and hung out. When I got ready to do this documentary, I wanted to get some young, fresh, Gen Z folks that were on the cusp of coming into adulthood to talk about their experiences. [My crew and I] just went to the West Village and we came across a group of 18- and 19-year-olds that were voguing and hanging out and they seemed fun. I asked, “Could we follow you guys?” They were like, “Sure!” We literally spent from, like, 1 o’clock in the afternoon to almost 1:30 a.m. in the morning following this group of young queer people—nonbinary, trans—around the West Village. We got a chance to see them vogue in front of the police in Union Square. It was an adventure.

Nelly, who is one of the youngest members of the group, was actually a minor. We found that out because, apparently, Crime Stoppers put her on a poster online and around the city for a 15-year-old who had gone missing. I was a little perplexed at first, like, “Oh my god, she’s 15?” She had lied to us and told us that she was 19. I was concerned. We tried to figure out where to find her for a couple months. Eventually, she created another Instagram account and Ivy [one of the other dancers] was able to get a hold of her. She said she couldn’t talk because she was using a friend’s phone to make the account so she told me I could meet her at her biological mother’s house. I brought my friend, who’s also one of my videographers, and we captured it in real-time. I was just really glad that nothing horrible or deplorable happened to her.

Fried: There is another trans woman you incorporated into the documentary, Dominique Fells. That was another incredibly powerful piece of the film to me. I was curious if you could talk a little bit about her inclusion. It’s footage from another source, so it almost felt like a piece of archival footage.

Rice: After I did the piece on Iyanna Dior, at the exact same time, we started getting this resurge of Black Trans Lives Matter. The image that people saw was a Black trans woman with purple hair and that was an image of Dominique Rem’mie Fells. I wanted to know more about her story, but it was really hard because we couldn’t find people who knew her. I started doing research, honestly, on Grindr. I set my location for Philadelphia and I started asking a lot of trans and nonbinary people, “Do you know Dominique?” Once I was able to find one of Dominique’s friends, we got in contact with each other. They said, “There’s a guy who recorded a piece on Dominique, but we think it’s taken down.” His name is Malcolm Lewis and he said he would be willing to hand over the footage as long as we can put it in a space where we can remember her.

The interesting thing about him filming Dominique is that he had just purchased a brand-new camera and, in his outreach office, he left the camera recording and forgot to turn it off. Dominique had walked by that day and was putting on her lipstick and makeup in the reflective part of that window, not knowing that a camera was behind her recording. He saw that in his camera, and then she came back around the next day walking the street. He said, “Hey, I accidentally recorded you. Can I interview you because I’m doing a YouTube show about people’s struggles with addiction.” She said, “Sure.” Two weeks later, after that recording, she was found murdered. One month after her murder, we contacted him. It really all happened within a two-and-a-half-month period.

Fried: Did that feel sacred, having that footage?

Rice: It really did. The eerie part of it is that Dominique had a past where she wanted to be an actress and a model. She always had dreams of wanting to be more. One of the last things she said to Malcolm was, “The next time you see me, I’m not going to be on YouTube, I’m going to be on your TV screen,” with hopes of getting out of her situation and being able to flourish in her dreams. Two weeks later, she was on the TV screen, but it wasn’t for her success, it was because of her demise and brutal murder. I thought it would be beautiful to honor her by telling her story. I didn’t want to focus on her drug use, even though I think the audience already knew what was going on. I decided to parallel her with Goldie, who was also a young, Black, trans girl and had the same kind of beginning as Dominique. One went in one direction and one went in the other direction. I wanted to show that differentiation and that parallel.

Fried: We see that, in this community, there is death, but then there is also life and joy and happiness. I think the documentary captures that really well.

Rice: One thing that I’ve realized in touring this documentary—we’ve toured in Portugal, Australia, Italy, the UK, all over Canada and all throughout the United States. Most of these spaces have been heavily White with few people of color. But one thing that I realized is that everyone had a liking to it because it spoke about the human condition of making it through adversity. It deals with subject matter that we all deal with: patriarchy, White supremacy, bigotry, ignorance. That’s a lot of stuff that we all, as a human race, can understand, but we’re just looking at it through another lens. It’d almost be like me watching a movie about the Holocaust and its aftermath. I may not be Jewish, and I may not have been born in that time period, but I can understand adversity and that’s something I would want to see anybody overcome. I think it’s the same way with the BLACK AS U R audience. They’re seeing that adversity as a part of the human condition and they’ve really taken a liking to it and an allyship to it.

Fried: It’s very interesting that you compare it to watching films about the Jewish experience. I am Jewish and, in hearing about the religiosity of these communities and why that causes friction with a lot of the LGBTQ population, I was able to relate that to the religious strongholds in my Jewish community and how they, too, create these communities of toxic masculinity and non-acceptance for people of non-binary identities. I had an eye-opening revelation about my own communities through seeing this film that was about a community that is so far removed from my day-to-day.

Rice: Right. I really commend my father. I grew up in the military, being around my dad, and we moved to Germany for a little bit of time. My dad made it a point to send me on a tour of a concentration camp in Strasbourg, France with a rabbi. I was able to parallel that experience with what my great-great-grandfather went through when he was a slave and emancipated at the age of 15 years old. I could learn that history, take it in, and parallel it to the experience of the Jewish people in that time period and even up to now with attacks on synagogues. I’m familiar with that because I’m familiar with adversity. I’m familiar with people’s ignorance. That’s why I felt that it was incredibly important for me as a Black, gay filmmaker to create something that is authentically coming from the spirit of a Black, gay creator.

Fried: When are general audiences going to be able to see BLACK AS U R? Is there a release strategy in the works?

Rice: There is a release strategy currently in the works. We have some distribution deals now with Billy Porter coming on board.

Fried: I think that Billy is going to make sure it happens, but I think everybody needs to see this film. For somebody who found this documentary incredibly eye-opening, for someone who feels they’ve been heavily educated by it, what would you say is the next step, especially for people who are outside of these communities, who want to be allies, who want to learn more?

Rice: I would definitely say look at your local LGBT community centers, especially those that deal in populations with people of color. There are also a lot of organizations that work with trans people, like the Hetrick-Martin Institute and The Door. On the BLACK AS U R website, we have a resources link that guides you to certain pages where you can find out more information. Also, just be open. Create spaces for people to dialogue about LGBTQ situations dealing with Black and Brown and Latinx folks. Support LGBT Black and Latinx artists and filmmakers posting on social media, go to screenings and events. Having our allies be in these spaces is a big help.

Fried: I want to thank you so much for all of your time and your efforts in making BLACK AS U R. It gave me my own revelations and I think a lot of people are going to feel similarly.

Rice: Oh, most definitely.

BLACK AS U R is currently seeking distribution.

Larry Fried is a filmmaker, writer, and podcaster based in New Jersey. He is the host and creator of the podcast “My Favorite Movie is…,” a podcast dedicated to helping filmmakers make somebody’s next favorite movie. He is also the Visual Content Manager for Special Olympics New Jersey, an organization dedicated to competition and training opportunities for athletes with intellectual disabilities across the Garden State.