Over a decade after his breakthrough performance in The Social Network, Jesse Eisenberg is one of the few actors left that still has universal name-brand recognition. He is forever an icon of the screen, has numerous credits on the stage, and has even contributed writing to The New Yorker. And yet, through all of that success, he still cannot escape how meaningless it can all feel.

“I struggle to feel like what I do is valuable and not just vain,” says Eisenberg. “My wife is a social justice activist and she teaches disability justice and awareness. When I come home from a great day signing autographs after she has spent the day doing something that I think is more socially impactful, it forces me to assess my pursuits.”

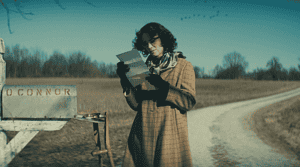

Despite the actor’s reserved demeanor, he is about to put what he calls “a personification of that debate” on full display. Based on his Audible Original of the same name, When You Finish Saving The World is Eisenberg’s directorial debut. The film stars Julianne Moore and Finn Wolfhard as Evelyn and Ziggy, a mother and son who don’t see eye to eye in their daily pursuits. Eisenberg may be behind the camera, but upon digging into the design of his characters, you realize he is still very much in front of it.

“The two leading characters have unusual and original voices,” explains Eisenberg. “That’s because I was not taking them from other movies that I had seen and liked, but I was taking them from something that I had not only thought about a lot but written way more in a different medium.” Eisenberg draws direct parallels from his own life to the characters on the page. “Ziggy is this shallow artist, which is the thing I worry about becoming, and Evelyn is this do-gooder who I aspire to be but find daunting. It’s their clash of values that is at the center of the movie.”

Ziggy is certainly an extension of Eisenberg, if a bit warped for modern day. Wolfhard’s character is an indie musician on a popular streaming platform, earning daily donations from fans worldwide. However, this easily recognizable internet stardom connects to Eisenberg’s anxieties about the cult of celebrity in a digital world.

“We’re living through this strange technological time where somebody can be beloved by thousands of people that they’ll never, ever meet.” Eisenberg looks down, still attempting to wrap his head around the phenomenon. “The kind of emptiness that that might bring, that you could both at once feel completely beloved and have no one to give you a hug and say, ‘that was amazing,’ that’s what Ziggy’s dealing with.”

Ziggy’s descent into his songwriting creates distance between him and his mother, the head of a domestic violence shelter who has devoted her life to activism. “He’s probably reacting to her not being interested in his own life,” continues Eisenberg. “This is what happens in families, you know? You create these toxic patterns.”

Taking inspiration from his work with director Riley Stearns in The Art of Self-Defense, Eisenberg wrote the characters to be blunt but sincere. “They’re both the leaders of their dominions. When they’re both in their element, they’re quite in control, but they’re missing something because they’re stuck in the house with somebody who just doesn’t appreciate the thing that they do so well.”

In anticipation of the film’s opening weekend, Eisenberg sat down with a fellow Jersey boy to have a conversation about adapting his own audiobook, collaborating with composer Emile Mosseri, and local kosher pizza, among other things. Here is that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

–

Larry Fried: The first thing I want to talk to you about is that we actually both grew up in East Brunswick, New Jersey.

Jesse Eisenberg: You’re much younger, right?

Fried: Yeah. [laughs] We never crossed paths.

Eisenberg: Where did you live, if you don’t mind me asking?

Fried: I lived off of [street name redacted], literally a few blocks away from the local high school.

Eisenberg: East Brunswick High School?

Fried: Yeah.

Eisenberg: Okay. So, I grew up…do you know Cranbury Road or Old Stage Road?

Fried: Oh, yeah. Speaking my language.

Eisenberg: Wow, and you moved?

Fried: Yes, I now live in [Jewish area name redacted].

Eisenberg: Are you Orthodox?

Fried: I am Modern Orthodox, yeah.

Eisenberg: Oh, you are? Okay.

Fried: Yeah. That’s really nice of you to ask, thank you.

Eisenberg: I like the kosher pizza place there. One of my best friends is Israeli and he has family in [Jewish area name redacted], so when I meet him there, we have kosher pizza. And it’s good. It’s, like, better than it should be.

Fried: Oh, yeah. I keep a kosher home, so—

Eisenberg: Oh, you do!

Fried: I ask all my non-Jewish friends to eat the kosher pizza and they’re like, “Dude, this is way better than most of the pizza in the surrounding towns.”

Eisenberg: Is there frozen kosher pizza?

Fried: There definitely is, but we don’t talk about that.

Eisenberg: Oh, okay.

Fried: I know that you had a tough time with school when you were growing up in East Brunswick, but I also know that you did some local theater when you were younger. I would love to hear about some of the positive artistic memories that you have from that time that inspired you and would go on to influence the actor that you would become.

Eisenberg: That’s so sweet of you to ask. I did children’s theater in Edison, so nearby. I’d be lying if I said I really liked the acting of it, I just wanted to be with my older sister, like a lot of younger siblings. She liked doing it and I was just doing it to be with her, but I really had no idea what I was doing.

Fried: [laughs]

Eisenberg: I probably didn’t know the difference between being on stage and off stage and I was not good in any way. Then I think I started going to theater camp with her, which was in Villagers Theatre in Franklin Township. I don’t know if you know—

Fried: Absolutely. A few of my friends would go on to act and direct stuff there.

Eisenberg: Oh, really? It’s a great, great place. I grew up going to summer camp there with my sister and I was cast as Charlie Brown. I remember thinking for the first time that I had some skill, because I had to audition for it even though I was in the camp. It gave me a little confidence. I was obsessed with the Phoenix Suns and wanted to be a basketball player, but I didn’t get the same kind of encouragement there. When I think back on it, you think “What do people wind up doing?” A lot of times it’s just the thing that they got encouragement for when they were 12, you know? [Acting], for me, was it. I got encouragement and was told that I was good at it, so I stayed with it.

Fried: That’s awesome. I’ll have to talk to my friends at Villagers, let them know they got a little shout-out.

Eisenberg: Please do, yeah.

Fried: I assume, during that time, you were also being exposed to films and filmmakers. Were there any filmmakers that you were exposed to during that developmental period that would go on to influence your directing style and who you wanted to be as a director?

Eisenberg: When I was just at the very end of my senior year of high school, I was cast in Roger Dodger and it was a co-leading role with Campbell Scott. I was on the set of the movie when I was 18 years old and I was trying to pick up everything I could possibly pick up: why they were moving the camera this way, what a gaffer does, if I could meet the composer, where they were editing, why it took so long to go from one location to another location. It was 20 years ago but I remember every crew member who worked on that movie because it was so indelible and impactful.

That movie’s style of filmmaking is similar to When You Finish Saving The World. That movie was made in this kind of naturalistic, run-and-gun style, and when you watch the movie, it feels homemade. It feels personal, it feels gritty, and it feels visceral. I was trying to go for a bit of a similar quality. My movie has a bit more of a satirical element, so there are things like zooms and long, awkward, uncomfortable pauses, but otherwise, I was trying to go for something that felt homemade and lived-in and real.

Fried: Speaking of your film, I know it’s based off of your Audible Original, which was a much more expansive story. It tackled three different characters in three different time periods. It’s very daunting for any filmmaker to adapt a story from one medium to a completely different one, let alone as their directorial debut. What were the challenges that came with that process?

Eisenberg: Again, thank you for such a thoughtful question. My background as a writer is in theater and I was never able to sit down and write a play. I always started with writing monologues from the characters’ perspectives because it allowed me to get into the headspace of those characters. It’s something that I have done as an actor. You start journaling in the mindset of the character and it gives you some insight into something that you wouldn’t have been able to think about otherwise.

I had written, essentially, a novel version of this story, so when I was sitting down to write the characters, their voices were in my head. The thing I like most about this movie is that the two leading characters have unusual and original voices. That’s because I was not taking them from other movies that I had seen and liked, but I was taking them from something that I had not only thought about a lot but written way more in a different medium.

Fried: Yeah, there is a sincerity to both of the characters, almost to a fault, that I think makes them really compelling to watch in the film. Was that on your mind when you were writing them?

Eisenberg: Yes, thank you. They’re both the leaders of their dominions. [Evelyn, Julianne Moore’s character], obviously, has a much more profoundly helpful dominion. She runs this domestic violence shelter and is responsible for dozens of people whose lives are very difficult. Ziggy [Finn Wolfhard’s character], on the other hand, is a god to 20,000 fans from Belarus to Bangladesh. When they’re both in their element, they’re quite in control, but they’re missing something because they’re stuck in the house with somebody who just doesn’t appreciate the thing that they do so well.

When I think about people who are very popular online, the thing I think about the most is––when they close the computer and they’re just in their house, what does that feel like? We’re living through this strange technological time where somebody can be beloved by thousands of people that they’ll never, ever meet. The kind of emptiness that that might bring, that you could both at once feel completely beloved and have no one to give you a hug and say, “that was amazing,” that’s what Ziggy’s dealing with. By contrast, his mother does this amazing work and her son refuses to show interest, but he’s probably reacting to her not being interested in his own life. This is what happens in families, you know? You create these toxic patterns. In terms of their sincerity, they both speak in these blunt ways that oftentimes get them in trouble.

Fried: It honestly reminded me a lot of your work with Riley Stearns in The Art of Self Defense.

Eisenberg: It’s funny you should bring that up. To me, that is the ideal acting part. I told Riley, “if we could shoot this over the course of a year, I would be happier than anything.” I love that style. I love people who are like that, I know people who are like that. There’s a part of me who’s very much like that, missing some social cues and speaking in a blunt way because you’re too scared to lie. You know what I mean?

Fried: Oh, absolutely.

Eisenberg: I just love that kind of thing. I would do that every day. There was an element of that [in When You Finish Saving The World], but Riley is pitching his movie in a different way. He’s creating a satire on modern, silly masculinity. This movie is aiming for something, I would say, more sympathetic to those characters. But I was definitely inspired by it.

Fried: I got to see the film twice and, on the second viewing, the line from Jay O. Sanders, “I live with a bunch of narcissists,” really stood out to me. I think it serves as a gateway into understanding what this movie’s really about, which is the narcissism of these two main characters and the victims of this narcissism. They both come from this place of privilege even though they think their intentions are good.

Eisenberg: Right.

Fried: In other interviews, you’ve spoken about how the script is based on your own experiences as a person of celebrity and how you debate the value of your own work. I’d love to hear more about how you channeled those experiences and navigated them in terms of writing the film.

Eisenberg: Like a lot of people in the arts, I struggle to feel like what I do is valuable and not just vain. I’m so often doing things, even an interview like this one, where I’m talking about myself and promoting a movie I did and I walk away from them thinking like, “was that a good thing to have done, to talk about myself and promote a movie I made?” There’s nothing inherently wrong with it, but it makes me question my own set of values and whether I am doing the right thing. My wife is a social justice activist and she teaches disability justice and awareness in New York public schools. When I come home from a great day signing autographs after she has spent the day doing something that I think is more socially impactful, it forces me to assess my pursuits.

This movie is a personification of that debate. Ziggy is this shallow artist, which is the thing I worry about becoming, and Evelyn is this do-gooder who I aspire to be but find daunting. It’s their clash of values that is at the center of the movie. The question that the movie raises is, “how do you live with somebody that you don’t appreciate? What do you owe to your family even if the way they think about the world is anathema to you?” Towards the end of the movie, Evelyn discovers that Ziggy is actually quite a good singer and he’s charismatic and, you know what, on his terms, he’s good and worthwhile. And Ziggy realizes she has created this incredible thing just like he has created this incredible thing. Even though it’s not the thing that he would pursue, there’s so much value in it. That’s, in some ways, letting myself off the hook.

Fried: My last question is about the music. Emile Mosseri is a fantastic composer, but I’d love to hear specifically about the collaborative process between you, Emile and Finn. I’d love to hear the particulars of how a song like “Pieces of Gold,” which becomes a motif throughout the film, is created between all three of you.

Eisenberg: That’s, once again, such a generous question because it allows me to talk about my own dormant musical desires. I wrote that song with piano and guitar and synthesized instruments. I sent it to Emile and he told me that it sounded like something a teenager in a musical theater class would write.

Fried: [laughs]

Eisenberg: So, he took my lyrics and wrote an adult version of the song that would be good in a movie. Emile is amazing. He had just finished doing the soundtrack for Minari, which is this very lush, rich, traditional kind of score. We were talking about how to make this feel different and my thought was that the soundtrack should come from Ziggy’s instruments. Ziggy’s a 17-year-old kid who would’ve picked up a little Casio along the way and maybe a MIDI keyboard. Emile got some lo-fi instruments and started making the score, so the basis is actually just on a footlong Casio keyboard from the early 90s. He’s so talented and so adept that he made that concept work.

Then, Finn came in and made [each song] his own. We did that throughout the whole process. I would pitch Emile my versions, he would be very polite and do his own, and then Finn would come in and make it his own. But, even more than that, we would sometimes just ask Finn to improvise a song in character. There are a few moments in the movie where he does that and it’s just so brilliant and funny. Finn is a very adept and accomplished singer/songwriter, and so for him to riff in character was just thrilling to watch.

Fried: Jesse, thank you so much for your time. The film is really fantastic for a debut.

Eisenberg: That’s so nice, and we have so many nice connections. Thank you so much.

—

When You Finish Saving The World will release in select theaters on January 20, 2023 courtesy of A24.

Larry Fried is a filmmaker, writer, and podcaster based in New Jersey. He is the host and creator of the podcast “My Favorite Movie is…,” a podcast dedicated to helping filmmakers make somebody’s next favorite movie. He is also the Visual Content Manager for Special Olympics New Jersey, an organization dedicated to competition and training opportunities for athletes with intellectual disabilities across the Garden State.