When Texas Governor Greg Abbott appeared on screen at the SXSW premiere screening of Plan C, hissing began to emerge from the audience. Not exactly the state pride one would expect at a hometown screening. Well, for director Tracy Droz Tragos, that literally came with the territory.

“Texas has been at the forefront of [abortion] restrictions,” she says from her hotel room in Austin. “Things are getting cut off, you know.” As she says those words, the state court is exploring a potential reversal on long-standing federal approval over access to the abortion pill.

During what has been, and still is, a scary time for reproductive rights in the United States, Tragos traveled to over 14 states and shot “over 300 hours” of footage following the lives and efforts of the Plan C organization. Founded in 2015, the group works nationwide to provide access to the abortion pill, even in states where the pill has been outlawed.

The documentary, hot off of its World Premiere at Sundance, screened multiple times at this year’s SXSW Film & TV Festival and even held a pop-up event platforming various local, pro-choice organizations and nonprofits.

“It means a tremendous amount to be invited to come here, to be able to share [Plan C] with audiences, and to be part of spreading the news that there are still options and there are people still working very, very hard to increase access no matter what,” said Tragos.

The plan is for Plan C to be available on streaming by the Summer. Tragos wants to give people the opportunity to “see it in the privacy of their homes,” in line with the real risks facing women seeking an abortion. “There’s a risk-averse [entertainment] landscape out there, but nonetheless, we’re persisting.”

Tragos sat down with GVN to discuss the film’s inception, the responsibilities of capturing anonymous subjects, and the importance of being nimble when shooting independently. Here is that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Something that struck me during the screening was hearing hissing in the audience when [Texas Governor] Greg Abbott appeared on screen. It suddenly made it clear to me that this movie, in a way, is a Texas story. Since we are at South By Southwest, can you talk about the importance of this film screening in Texas? I don’t think a lot of people would recognize it on face value.

I mean, of course, Texas has been at the forefront of a lot of these restrictions. It means a tremendous amount to be invited to come here, to be able to share it with audiences, and to be part of spreading the news that there are still options and there are people still working very, very hard to increase access no matter what. I hope that message gets out there. Things are getting cut off, you know. There’s a lot of fear about even talking about this. I hope, maybe, if you can’t talk about buying abortion pills, you can talk about a movie instead.

Where did your story with Plan C begin?

It began back in 2018 when Kavanaugh was appointed to the Supreme Court. I wanted to research what folks were doing to plan for Roe being overturned because it looked like it might happen. It was my own interests, in part having made a film a few years prior [Abortion: Stories Women Tell] about the hoops folks had to jump through to access care even when Roe was in place. The fact that the writing was on the wall looked like it would result in so many more restrictions. I met Francine [Coeytaux, co-founder of Plan C] by reaching out to her on LinkedIn. She responded right away––she must’ve had her notifications turned on or something––and she agreed to meet. She’s also that kind of person. She’s very open to meeting new people and being very open about her work. That’s part of how she’s been able to do the things that she’s been able to do.

That perfectly brings me to my next question, which is about Francine Coeytaux [co-founder and co-director of Plan C]. She’s such a big part of not only the movement, but of this film especially. What was it like filming with Francine and working with her through the lens of her role as the subject of a documentary?

Well, she kind of takes over. She probably, in another life, should be a director. But I appreciated that personality, that there are people like her who are loud because they can be loud, who have big ideas, who are disruptive. I know that sometimes she’s seen as being too loud or too disruptive, but I think it takes people like her to make change and make things possible. There are other people working in different kinds of ways and they’re important also, so it’s not to say that that’s the only way change happens, but people like her are important to the equation. She can be a bit of a pain in the ass, but she can also be a joy and, ultimately, she’s one of my favorite people.

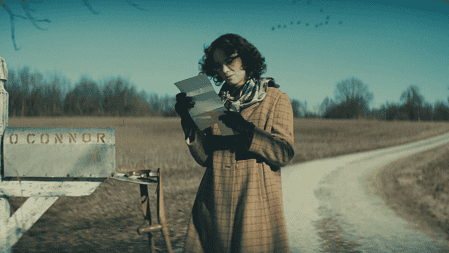

We have to talk about one specific scene where Francine is walking around a college in Texas and placing stickers in discrete locations. Can you talk to me about shooting that scene in particular and what that experience must’ve been like, trying to capture that covert action?

That’s the thing about Francine. She wants to affect change in whatever way she can. This was a way where we were secretly going to put these stickers in all these different bathrooms. Thousands of stickers went up during that trip and they all had a barcode on them that sent you to a page with more information. I have to say it was strange to be following her around with a camera. We tried to keep the camera discreet and she had her hat on and had her sunglasses on, but we were all going into the same bathroom where she was putting these up, so that felt a little weird. There was one moment when she forgot to lock the door, so someone came in and saw all three of us in the bathroom. I remember it was someone who was working in the cafeteria and he just looked, saw the three of us, saw the camera, and just went, “Uh, nope!” and turned back around. I wonder what he thought, bless his heart. It was fun, but it was also serious too because we really, really wanted this information to get out there.

Switching gears completely, there are a number of anonymous subjects in the documentary whose faces are not shown at all. As a director, can you speak to the responsibilities of having to be a face for the faceless, as well as the challenges of trying to capture anonymous subjects while protecting their safety?

It’s a balancing act, is the best way to describe it. I hope that I haven’t done anything to bring harm to their work. I think everyone who participated in the film did so with a personal risk calculation and participated to the extent that they felt safe. At the same time, I think we all knew that, with the film’s release, it’s hard to know what kind of bad actors are out there and what bad actors will do, so it’s also a bit of leaping into the unknown. Everyone participated with the intention of wanting to get the word out there and sharing the “why.” It’s not like I’m doing an undercover sting operation and actually trying to expose something. I’m in partnership with the people who are anonymous. That’s certainly the way that I would prefer to work as a director than trying to expose someone.

Some of the redacted names in the film reveal themselves during the credits. What was the process in which these subjects decided that it was time to put their name on the project?

Ultimately, as things got more and more restrictive, there were some in the film who came out and became more angry about what was happening. They wanted to say, “No, this is enough. I’m doing this work, I’m doing it out in the open.” That certainly happened over the course of filming, that the attitudes changed as things got worse and worse. Even one of the doctors who remains anonymous, she’s at the same time gotten more angry and wants to do more. The levels at which people want to put themselves out there are different and I think it is at everyone’s personal discretion, whether they have little kids at home, whether they can be out there or not.

We spoke after the screening and you told me that you shot footage in 14 different states, which is remarkable. What are the difficulties in coordinating shoots that took place in so many different states with so many different levels of restrictions?

I appreciate the question very much because I think you see the end result and folks don’t realize that a lot goes into it. It’s a bit of a hat dance and requires being nimble. There were, honestly, more times than I care to remember where we would arrive somewhere only to be told that what we had planned wasn’t able to happen because someone got COVID. Flights also got canceled in the midst of shooting and we would be stranded and couldn’t get to where we wanted to be. I’m an independent documentary filmmaker, so in some ways, I’m able to be more nimble and not ask someone for permission, but it also ends up that things get to be more expensive and it can be a punch to the gut when you’re like, “Oh no, I just spent all that money and I have nothing to show for it, and I’ve got to do it all over again.” That happened a lot, but that’s insider baseball. I do appreciate the question though because it wasn’t easy.

From the sound of it, you likely had a very limited crew going to all these different places. One camera operator, one sound mixer, if that. I’m sure that helped a lot in terms of being nimble.

Yes, but it, frankly, is also the way I prefer to work. I’m not a cinematographer, I don’t think my camera work is very good. I prefer to bring someone with me and hire a crew, but a trusted crew. I had worked with both the primary DPs [directors of photography] before and we built a language through working together that didn’t always have to be said out loud, so we could be more nimble with each other. Sometimes we didn’t have a sound person because I couldn’t bring someone on or I couldn’t afford it. It all depended.

Sometimes it can feel like a documentary is never ending because the story is always continuing. With the place we’re at with this topic in particular, you could’ve been working on this documentary for another year, two years, three years, and more would’ve developed. What made you decide to end the documentary where you ended it and that this was the time to send it out to the masses?

It was actually very tricky. Had I been working in collaboration with a distributor, I think I would’ve raised the question, “Should I keep filming?” because things are continuing to happen, but I didn’t. When Roe fell, I felt an urgency to share the news that there was this network of people who had come together to make sure this option was possible no matter where you lived. This was important news that wasn’t getting out there. I still heard the predominant narrative that people had to travel to clinics rather than potentially this medication coming to them for a lot less money and a lot less disruption. I felt it was important to get the word out that this was an option. That’s why I put the camera down. I had a lot of footage, certainly enough for a film. It was over 300 hours.

300??

Yeah, 300 hours.

Well, you put it together into something really spectacular. As a last question, what are the plans for the film right now? Where are you at in terms of getting this out to people?

We’ll go to more festivals. I’m excited to be bringing it to places where there are restrictions––to red states, frankly. I mean, we’re bringing it to Ohio. Someone was in the audience yesterday from Tennessee and they were like, “We’ve got to have it in Nashville! Can you bring it to Nashville?” And I was like, “Of course, that’s where we want it to be seen.” But ultimately, my big, big hope is to have it on streaming so that folks can see it in the privacy of their homes if they don’t feel safe going to a festival or a theater and see it. I’m working on that right now, but it’s not easy. [With] a film about abortion, there’s a bit of a reluctance. There’s a risk-averse landscape out there, but nonetheless, we’re persisting. I hope by the summer we will make it possible, one way or the other, for folks to see it widely.

Plan C screened as part of the Festival Favorites section at SXSW 2023. It is currently seeking distribution.

Larry Fried is a filmmaker, writer, and podcaster based in New Jersey. He is the host and creator of the podcast “My Favorite Movie is…,” a podcast dedicated to helping filmmakers make somebody’s next favorite movie. He is also the Visual Content Manager for Special Olympics New Jersey, an organization dedicated to competition and training opportunities for athletes with intellectual disabilities across the Garden State.