The golfing subgenre of sports movies is a very limited canon, and even more limited if you’re looking for inspiration. People are quicker to recall Happy Gilmore and Caddyshack over Bagger Vance or The Greatest Game Ever Played. Hell, if we’re basing this on notability, Space Jam is more of a golf movie than Tin Cup.

The Phantom of the Open may not ever reach the prolific levels of Michael Jordan or the Looney Tunes, but it does find a unique middle ground amidst the competition, or lack thereof. It’s a story based in history, but also in absurdity; it balances family drama and class prejudice with fantasy sequences and hokey disguises. Oh, and there’s golfing in there too. While you can see these tropes across many different genres, it all works together here to create a new kind of alchemy. Though this surprisingly complex balancing act never fully coalesces, it does make for an entertaining and fresh take.

A lot of this boils down to the events themselves, a story so madcap that the only person who can take credit for that is the subject himself. Maurice Flitcroft’s turn from humble crane operator to humble sports hero after scoring the worst result in British Open history is what movies were made for. It just took the right minds to take the reins. Producer Tom Miller and writer Simon Farnaby saw the appeal years ago, working together on a biography that was published under the same name in 2010. Years later, they have brought the story to the silver screen, where it belongs.

But another part of it is taking these events and doing something unique with them. In interviews, Farnaby often spoke about his desire to elevate the story above the “kitchen sink” style of British drama, a genre that puts realism and disillusionment at the forefront. It’s not an obvious choice, especially given Flitcroft’s background, but, given Farnaby’s work on the iconically wholesome Paddington 2, and the reportedly whimsical Wonka prequel, it was the right one.

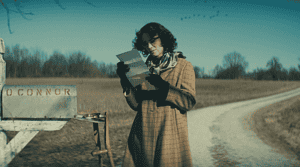

Luckily, Farnaby found a director who could visually bring out what he was looking for. Even with his darker directorial resume, Craig Roberts imbues the entire film with a lighter, brighter sensibility: rich colors, posh costumes, soft lighting, and a bangin’ soundtrack. He even includes a number of dream sequences, the highlight being one that can only be described as the golfer’s equivalent of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” One almost wishes the creative team went further with the fantasies of the character. They excellently juxtapose Flitcroft’s greater ambitions with his still-developing skills. Still, the stylistic choices we do have, plus a few additional flares here and there, give the film a cinematic pulse.

Things are a bit less cohesive in terms of tone. While it’s admirable that Farnaby and Roberts attempt to balance silly antics with deeper pathos, they don’t often blend. This isn’t only in terms of execution, but literally in terms of structure. Most of Maurice’s funniest moments, portrayed with a humble wit from Mark Rylance, are exclusively on the green; when Maurice returns to his family, things are more tender. It feels like two distinct modes, and one is committing harder than the other.

Toward the second act, Maurice’s son Mike, an earnest Jake Davies, begins to rise up the corporate ladder at work. However, his upper-class colleagues mock his father’s embarrassing performance and subsequent removal from the Open. This association forces Mike to distance himself from his family, which comes to a head in the third act. It’s touching, if a bit predictable, and everyone is giving the drama the weight it deserves. Sally Hawkins, in her second collaboration with Roberts, especially works her magic. One particular beat toward the end will make plenty of people well up.

With all of that hitting home, Maurice’s comic antics throughout the second act really compare. Flitcroft was a hoaxer, repeatedly attempting to compete in the Open by donning disguises. It’s obviously very amusing to see an accomplished actor like Mark Rylance play it silly, complete with a Benny Hill-esque golf cart chase. But, harkening back to an earlier comment, they could have gone so much farther. This sentiment is especially true here considering these antics make up a relatively small portion of the runtime. The aforementioned cart chase, for example, ends rather abruptly. It’s almost as if they had a punchline but got there too quickly for it to actually hit. One has to wonder where Roberts’ stylistic flourishes went as well.

Pervading the entire film is this notion that Farnaby and Roberts played it safe in accentuating the absurdity. But maybe that’s why they still feel like the perfect storytellers to tackle Flitcroft’s journey, which feels more inspirational than your usual underdog story. Flitcroft doesn’t skyrocket from rookie to all-star overnight; even at the end of the film, he still needs practice. But that’s what keeps the story attainable. People connect to Flitcroft because he has room for improvement, like so many of us. Neither Farnaby or Roberts have fully reached their pinnacles as individual talents, though they come closer together than apart, but that’s okay: it just means there’s room for improvement.

The Phantom of the Open, a Sony Pictures Classic release, is now playing in New York and Los Angeles, with a wide release soon to follow.

Though incohesive at times, this entertaining and funny romp makes up for it in genuine inspiration and plenty of fun stylistic choices to keep you engaged.

-

GVN Rating 7

-

User Ratings (0 Votes)

0

Larry Fried is a filmmaker, writer, and podcaster based in New Jersey. He is the host and creator of the podcast “My Favorite Movie is…,” a podcast dedicated to helping filmmakers make somebody’s next favorite movie. He is also the Visual Content Manager for Special Olympics New Jersey, an organization dedicated to competition and training opportunities for athletes with intellectual disabilities across the Garden State.