(Welcome to “Notes on a Score,” GVN’s interview series highlighting the composers and musicians behind some of the year’s most acclaimed films and television series.)

When asked to describe how he designed the piano part in his score for 2023’s Dead Ringers, Murray Gold lifts his hands. As he rolls his fingers across the keys of an invisible air piano, he is brought right back to his initial freehand scoring sessions for the series, performed in the height of the pandemic.

“I’m playing these really big chords, probably eight-note chords, and just spreading them out and letting them ripple,” the British composer says, enamored with his memory of the process. “It just felt so connected to what I was watching.” He stays on one part of the invisible keyboard, recreating the score’s motif of holding on a minor chord before resolving to a major chord. “It was like, ‘Is it time to move off yet? Is it time? Is it time? It’s time. Okay, let’s go.’”

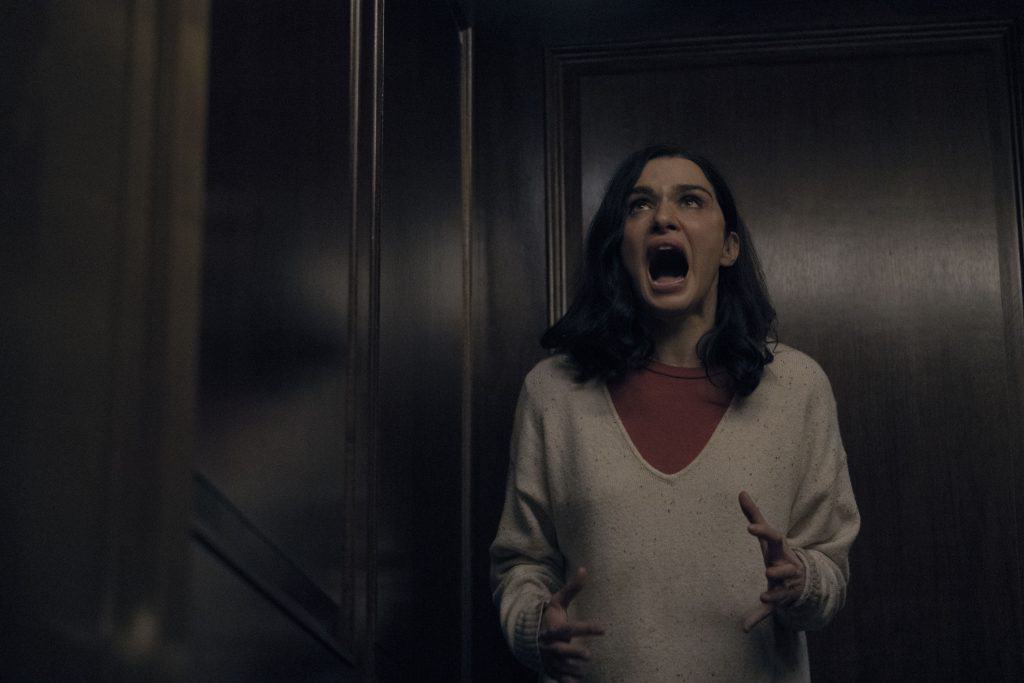

It’s one of the foundational elements of Gold’s score for the new miniseries, a reimagining of David Cronenberg’s original drama now starring Rachel Weisz in the dual role of Beverly and Elliot Mantle, twin gynecologists with severe codependency. To reflect the rampant instability within both sisters, Gold incorporated a “glissando-ing piano” that was, rhythmically, “very out of time.”

“I would literally sit and watch the episode and play freehand, really, around this chromatic up and down and just let that evolve in the purist musical way possible.”

When Gold was first approached for Dead Ringers, he was initially told he would have three weeks to complete all six hour-long episodes – thankfully, production time was extended after the fact. Still, with no temp score nor a single full viewing of Cronenberg’s original film to set precedent, Gold had to design the series’ sound entirely from scratch. Based on how excited he sounds describing his experience, this jolt of creative freedom was the best possible starting point.

“I think, in the most beautiful way, they just wanted me to respond to it,” Gold recounts. “They didn’t want to guide me in any direction.” He also notes that there were no spotting sessions, which he surprisingly appreciated despite being a common industry practice. “It just kills all the spontaneity, all the instinctive responses that you might have to something, all the joy of creation. Don’t cut out the favorite part of the job, which is the discovery.”

Other elements in Gold’s score include dark synthesizers, rhythmically syncopated vocals, and strings recorded by a North Macedonian orchestra. It all culminates into one of the most distinct scores in television this year, despite relatively little fanfare. This may be because you can’t hear it outside of Prime Video.

“For about a decade now, I haven’t allowed anything that I’ve written to be released separately,” explains Gold, disregarding his extensive collection of releases as the previous composer on Doctor Who. “I just feel so strongly that the score belongs to the picture and that’s what it’s for.”

Gold collaborated closely with series creator Alice Birch as well as Weisz, who also served as an executive producer. The three of them shared, as Gold describes, “a telepathy” that made working together an incredibly enjoyable experience. “At one stage, I said, ‘Have you read Susan Sontag’s essay about camp?’ And they just both started laughing. They just said, ‘Camp is very important to us. We’ve talked about it a lot.’ I was like, okay, enough said.

“They were literally the best bosses you could ever imagine having,” he continues. “I’ve known Rachel for a long time. She’s a phenomenally courageous person that doesn’t fear anything. She’s also an amazingly complicated person and she’s not afraid to wear her complexity. Alice is a fantastic writer and the two of them together are brilliant.”

In this extensive and exclusive interview with Geek Vibes Nation, Murray Gold goes in-depth on his creative process, the power of fluctuating between major and minor chords, and his undying love for The White Lotus. Here is our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Let’s just start from the very beginning. Talk to me about how you came to Dead Ringers.

My agent called and they said, “Can you take a look at this show? It’s called Dead Ringers and is based on the movie from the ‘80s by Cronenberg,” which I knew all about. I never saw the movie, but I was a really big Cronenberg fan. I had seen Videodrome and The Fly. I actually met Jeremy Irons once at the Emmys in 2006 and I completely lied to him. I just went up to him and said, “I’m such a fan of everything you do. All your choices are so edgy. I loved Dead Ringers,” and I’d never seen it. [both laughing] I still haven’t. But I love the idea of it.

Get all the skeletons out of the closet now, Murray.

I don’t know why, it just came out of my mouth. You know, the kind of shit that just comes out of your mouth without you even thinking about it to someone you’ve never met before at a party. I think I was just like, “Oh look! There’s Jeremy Irons. I want to say something to him. What shall I say?” Anyway, he didn’t spend very long talking to me. [both laughing] But yeah, Christine said that Rachel Weisz is doing [Dead Ringers] and it’s for Amazon and it has to be done in three weeks.

Woah!

I said that it would depend on how I responded to it. If it was instant, then it would be possible. But, obviously, I didn’t know anything about it. So, I watched it and I just really, really loved it from the get-go. It blew me away, actually. I was like, “This is really fucking good.” Then, I really quickly wrote an email to Alice [Birch, the series creator] about what I would try and achieve. I do find that working fast is a really useful thing – spontaneously responding to something, letting your instincts do their work, and not really thinking about it too much except from a gut level. It was so clear. People might say it has a difficult tone, but it seemed so clear to me what it was and how I could do the music. I fired off about 10 tracks really quickly and sent them to Alice. The response was positive.

What did you initially receive? Did you get a picture lock of every episode?

The first three episodes were there, but I just wanted to focus on Episodes 1 and 2. I didn’t want to go and score the whole series immediately. I wanted to let it sink in a little bit, or as much as it could in about two or three days. It sort of throbs with this cleverness, a theatricality. It was brilliant. It was dazzling. It had this confidence. It was edgy and it had a perspective that was difficult to place. It was a, kind of, godlike perspective where it’s a passive detachment, an attitude toward suffering that was simultaneously caring and dismissive. It had this complete instability, which is what I think gives it a sense of camp. I was on the edge of laughter all the way through and, at the same time, I was on the edge of screaming.

I’m always interested in the relationship between the edit and the score, but it sounds like they had the edits locked by the time that you were making the music.

Yeah. Edits locked and no temp score.

What a dream.

Yeah, I know, right? Exactly. I think, in the most beautiful way, they just wanted me to respond to it. They didn’t want to guide me in any direction. If there was one tune at the beginning that I heard, that was the only thing that there was in it. That’s how I prefer things to be.

What was that initial response from you? Where did inspiration strike for how this show was going to sound?

Well, I just got someone to go, “om-nom-nom-nom-nom-nom-nom-nom-nom-nom-nom.”

[laughs]

That was the first thing I did. I wanted to capture the ravenous appetite. But I knew that there would be more than one kind of music involved. First of all, there was a glitzy, moneyed feeling [in the show]. There’s sort of an Upper East Side, New York thing, and I lived in New York for 12 years, so I know it really well. There were things about the trappings of wealth, but there was also the visceral stuff, the instability. [I added] glissando-ing piano [in the score that was] just very out of time and a bit lost. I would literally sit and watch the episode and play freehand, really, around this chromatic [chord progression] up and down and just let that evolve in the purist musical way possible and then tidy it up a bit. Then, there was a sort of 2023-thing about it, which was the technology, [so I added] synthesizers to give it that sinking feeling. Then, we went and recorded some strings with The FAME’s Orchestra in North Macedonia. It was all over Zoom, but I’d worked with them before.

I have a really specific attitude toward scoring, which is that everything is about the writer’s intention and achieving that. I’m sometimes less concerned about what something sounds like. I’m more concerned with what it’s saying or how it’s illuminating the intention. That’s everything that I do. I think, in some way, because [Dead Ringers] was smaller, it was allowed to be more beautiful. I’d be sitting watching it, and I’d just think to myself, “Oh, yeah. This is very precise.” But at the same time, it’s also beautiful. I don’t care a lot of the time if something’s beautiful or not. It has to functionally achieve its aim, almost to the extent of not liking separating score from the film. For about a decade now, I haven’t allowed anything that I’ve written to be released separately.

Oh, wow.

Not that anyone would want to, but if they did want to, they can’t get various things that I’ve done the music for. I just feel so strongly that the score belongs to the picture and that’s what it’s for. You could say, “Well, I want to have the picture come back to me at night.” I don’t know, I just stopped doing that.

Let’s talk a little bit about Alice Birch. What were the conversations with her like in terms of illuminating what her goals were with the show?

Well, she put them all on the screen. She didn’t have to say anything. This is another thing. I’m not a big one for spotting sessions. I feel like talking about spotting, directors talking through what they want, it just kills everything. It’s so draining for a musician. I can tell you that the two worst things are temp scores and directors going through everything that they want. It just kills all the spontaneity, all the instinctive responses that you might have to something, all the joy of creation. Can you imagine what it feels like, as a composer, to receive something that has already gotten to the point that it can’t be bettered? All that can happen is it can be a bit more coherent. [When you’re given] a score drawn from 75 pieces of third-act Hollywood stuff that has been superbly edited so that every beat of it hits, all you can do is say, “Well, I hope I can get it to be as good as that.”

The temp music monster is an ongoing discussion on this series. I talk to almost every single composer about it.

It can be helpful if your employers are not sold on it, if they don’t want it replicated to as close to as is legally possible. But if that’s what they want, you may as well just feed all that information into an AI machine and have it regurgitate—set the settings to legal. [laughs] Don’t cut out the favorite part of the job, which is the discovery. This moment of “I think I’m there. I think it could be this, but what if we add this?” and, “Oh, there’s a language forming!” It’s bonding with the picture in a way that’s really exciting.

I love how you just described that.

Going back to your original question, I would come up to [my studio] and Alice, Rachel [Weisz], and Kendall [McCarthy], who’s one of the producers, would meet with me over Zoom. They were literally the best bosses you could ever imagine having. Really wonderful people. Lovely, brilliant, smart, witty, charming people. There was a sort of telepathy, really. At one stage, I said, “Have you read Susan Sontag’s essay about camp?” And they just both started laughing. They just said, “Camp is very important to us. We’ve talked about it a lot.” I was like, okay, enough said. It was a very artistic, beautiful experience.

It sounds like Rachel was involved with every step of the music.

Yeah. I’ve known Rachel for a long time. She’s a phenomenally courageous person that doesn’t fear anything. She’s also an amazingly complicated person and she’s not afraid to wear her complexity. Alice is a fantastic writer and the two of them together are brilliant. They’re both incredibly articulate, charming, emotionally complicated, but they’re easy to read, in a way. They have a clarity about them, both of them. They’re very illuminated people.

I do want to ask you about the fluctuation between major and minor modes. You mentioned the chromatic work on the piano earlier––

Well, that’s the ultimate instability.

Right! I noticed the strings constantly go in and out of major and minor modes as well. What was it like being able to move so freely between those two very different tonalities?

That’s a really great observation. I don’t even know if it was conscious. I started talking about instability and there’s nothing, in the Western tradition, more unstable than losing your sense of whether you’re in the major or minor. Going between them felt so natural to me, especially on this show. It’s the sound of everything. The division into major and minor in Western scales is a sort of hard-and-fast rule where we just say, “Oh, the major scale is happy, and the minor scale is sad.” But the blues has always gone in and out of the major and minor, and that’s what gives it its bittersweetness.

There’s a particular pattern, especially in the piano, where you’ll start with a note, then go just one half-step down, then back up to the note, then one half-step up, and then back down to the note. It feels like the theme for the twins. Did that progression come from the freehand or did you want to keep it within a very tight oscillation?

I’ve got to say that some of it’s a bit OCD. It’s like I haven’t finished, I have to get back [to the first note]. I’m playing these really big chords, probably eight-note chords, and just spreading them out and letting them ripple. It just felt so connected to what I was watching. It’s like, “Is it time to move off yet? Is it time? Is it time? It’s time. Okay, let’s go.” There’s a really strong sense, dramatically, of “when are we feeling comfortable again?” I always think about drifting away from home and coming home, and there are all kinds of ways that that works in music, the concept of ‘home.’ It can be rhythm, it can be intonation, it can be “are we back with a melody that we recognize as being home?” You set up the idea of home quite early on and then, just like you would in a classical concerto, the further you drift away from it, the more it’s necessary to reestablish it when you come back to it. We’re always playing with these ideas of home as composers.

I want to talk a little bit about the FAME’s orchestra, who were the string players, but also Alastair King, who was your string orchestrator. Can you talk to me about how both of them came to the project and what they contributed?

Alastair King is a fantastic collaborator and a really, really good orchestrator. He works on literally hundreds of big Hollywood films. We’ve had a really close working relationship since my last season of Doctor Who with Peter Capaldi, so going on a decade. Me and Alastair came across FAME’s during lockdown when studios were unavailable in the UK. At that time, the guys in the FAME’s orchestra were doing their sessions wearing masks. I support the Musicians’ Union in the UK and I don’t really like using orchestras outside of the UK. I hadn’t done that up until the lockdown, but it was necessary this time. We couldn’t record, we needed live instruments, so I broke a habit and did that.

There’s always a thing when you work with musicians from a different country. They interpret input differently, not from language difficulties, but from local, stylistic differences. I find that bending strings or [doing] bluesy strings can be awkward with formal orchestras, or people who are used to playing classical music or romantic music. Out of all the instruments, a string orchestra can be the most difficult to achieve that drifting tonality that you were describing. It’s easier with wind instruments. I think string players are so preoccupied with intonation that they really feel a bit lost, but FAME’s did it. We would ask them to do a long, slow glissando and then for everyone to meet [at the end]. They really nailed it.

Last question: I’m always interested to hear about what scores other composers are listening to. Is there a score you’ve heard recently that has been inspiring you lately?

The score for The White Lotus is the greatest TV score of the last 10 years. Season 1 was great, but the wings come out in Season 2 and it flies. Again, it’s a similar series to Dead Ringers in that it has an auteur at the center of it. So much television feels like somebody had a great idea, and you get a really good Episode 1, and then something was greenlit and then a bunch of people sat in a room and said, “How can we create content?” Nobody was saying, “How can I fulfill my life’s mission? How can I get out all the shit inside of me that I want to just burn into the screen?” There’s no sense of importance on-screen, but with The White Lotus and Dead Ringers, there’s just a sense of importance, the sense of “I have something to say, I will say it, nobody’s going to stop me saying it no matter what happens.” The White Lotus is such a fucking great series. I think it’s one of the greatest pieces of visual media.

Wow.

For me, it’s up there with The Godfather. And I know it riffs on The Godfather in the second season.

That’s funny, yeah.

It’s just brilliant, but then so is Dead Ringers.

Murray, truly, such an insightful and incredible conversation. I love the series’ music, and I want to thank you so much for your work on it.

I’m so grateful for you inviting me on, thank you for having me.

All six episodes of Dead Ringers are now available exclusively on Prime Video.

Larry Fried is a filmmaker, writer, and podcaster based in New Jersey. He is the host and creator of the podcast “My Favorite Movie is…,” a podcast dedicated to helping filmmakers make somebody’s next favorite movie. He is also the Visual Content Manager for Special Olympics New Jersey, an organization dedicated to competition and training opportunities for athletes with intellectual disabilities across the Garden State.